5 min read

› Larger view

By Ellen Gray,

NASA's Earth Science News Team

Warmer temperatures and thawing soils may be driving an increase in emissions of carbon dioxide from Alaskan tundra to the atmosphere, particularly during the early winter, according to a new study supported by NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). More carbon dioxide released to the atmosphere will accelerate climate warming, which, in turn, could lead to the release of even more carbon dioxide from these soils.

A new paper led by Roisin Commane, an atmospheric researcher at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, finds the amount of carbon dioxide emitted from northern tundra areas between October and December each year has increased 70 percent since 1975. Commane and colleagues analyzed three years of aircraft observations from NASA's Carbon in Arctic Reservoirs Vulnerability Experiment (CARVE) airborne mission to estimate the spatial and seasonal distribution of Alaska's carbon dioxide emissions. They also studied NOAA's 41-year record of carbon dioxide measured from ground towers in Barrow (the name recently changed back to Utqiagvik), Alaska. The aircraft data provided unprecedented spatial information, while the ground data provided long-term measurements not available anywhere else in the Arctic. Results of the study are published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

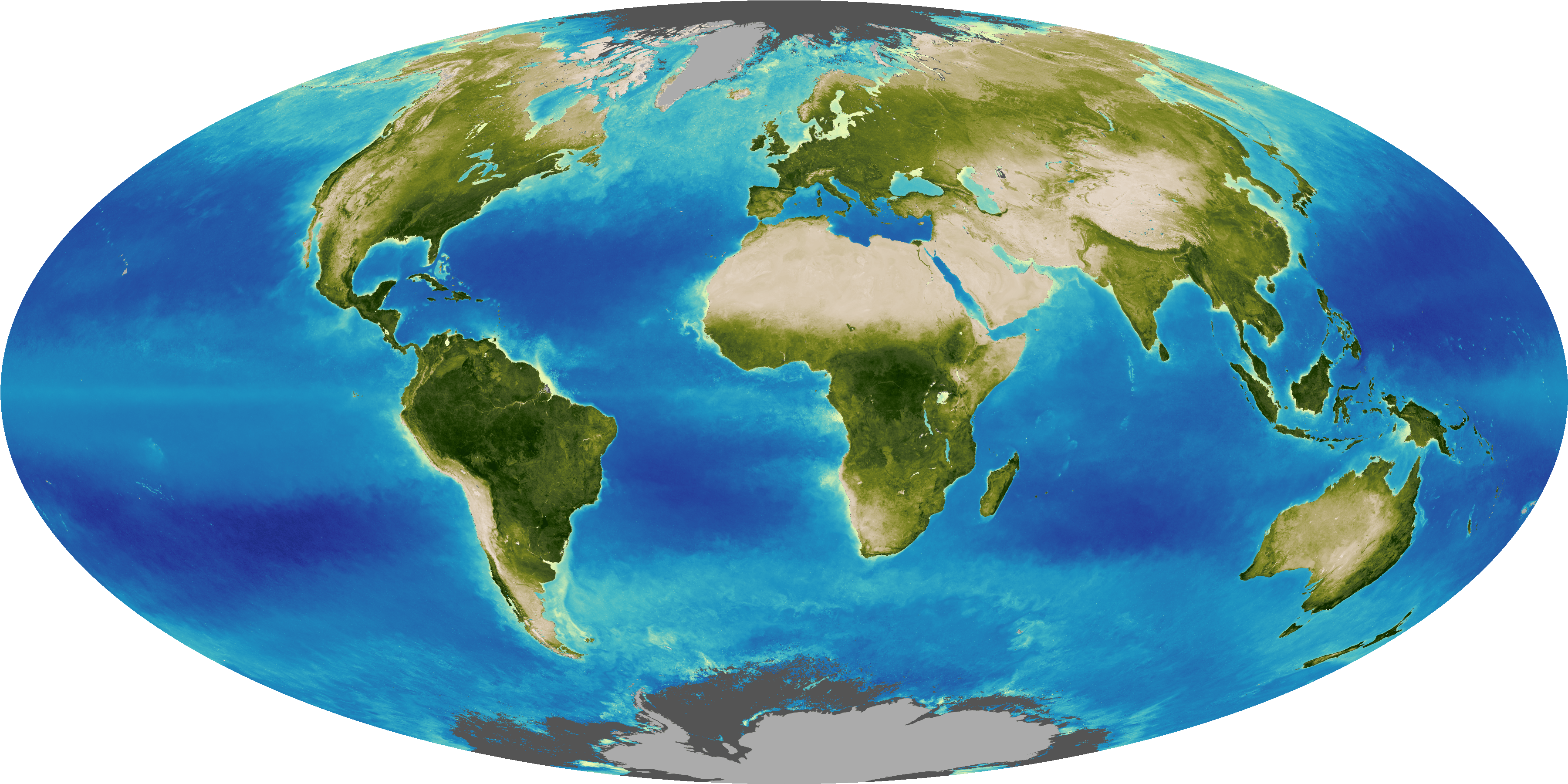

The soils that encircle the high northern reaches of the Arctic (above 60 degrees North latitude) hold vast amounts of carbon in the form of undecayed organic matter from dead vegetation. This vast store, accumulated over thousands of years, contains enough carbon to double the current amount of carbon dioxide in Earth's atmosphere.

During the Arctic summer, the upper layers of soil thaw and microbes decompose this organic matter, producing carbon dioxide. When cold temperatures return in October, the thawed soil layers begin to cool, but high rates of carbon dioxide emissions continue until the soil freezes completely.

"In the past, refreezing of soils may have taken a month or so, but with warmer temperatures in recent years, there are locations in Alaska where tundra soils now take more than three months to freeze completely," said Commane. "We are seeing emissions of carbon dioxide from soils continue all the way through this early winter period."

"Data from Barrow show steady increases of both atmospheric carbon dioxide and temperature in late fall and early winter," said co-author Colm Sweeney of the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences in Boulder, Colorado. "This new research demonstrates the critical importance of these long-term monitoring sites in verifying the subtle feedbacks, such as increases in carbon dioxide, which may amplify the unprecedented warming we are seeing throughout the Arctic."

CARVE flew an instrumented NASA aircraft to measure atmospheric carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases over Alaska from April to November in 2012, 2013 and 2014. These data, along with satellite data on the vegetation status and ground data to provide a year-round context and a long-term record, gave the scientists a detailed picture of carbon emissions at the regional level.

"One of CARVE's main objectives was to challenge the idea that carbon dioxide respiration stopped as soon as the snow fell and the land surface froze," said Charles Miller, a scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, and CARVE principal investigator. "The CARVE flights prove that microbial respiration continues in tundra soils months after the surface has frozen."

By comparing simultaneous measurements of atmospheric carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide, Commane and her co-authors split apart their estimates of the total carbon budget of Alaska into contributions from the three major sources of atmospheric carbon: burning of fossil fuels by people; wildfires; and microbes decomposing organic matter in the soil. In sparsely populated Alaska, the soil microbes were a much bigger source of atmospheric carbon than fossil fuel burning. Wildfires were a big source of atmospheric carbon in just one year of the CARVE experiment, 2013.

"Tundra soils appear to be acting as an amplifier of climate change," said co-author Steve Wofsy, a Harvard atmospheric scientist. "We need to carefully monitor what it's doing up there, even late in the year when everything looks frozen and dormant."

"The entire Alaska region is responding to climate change," said professor Donatella Zona of San Diego State University in California, who was not affiliated with the study. "Surface measurements suggest that the amount of carbon lost from Arctic ecosystems to the atmosphere in the fall might have been increasing over the past decades. By better capturing these cold season processes and putting previous smaller-scale measurements into a bigger context, this study will help scientists improve climate models and predictions of Arctic climate change."

Commane, Sweeney, Miller and their colleagues plan to expand on this work with NASA's Arctic-Boreal Vulnerability Experiment (ABoVE) field campaign, now in its second season in Alaska and northwest Canada. As part of the broader ABoVE effort, they will make airborne measurements of carbon dioxide and methane each month from April through October.

Media contact

Alan Buis

Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif.

818-354-0474

alan.buis@jpl.nasa.gov