Infrared Waves

What are Infrared Waves?

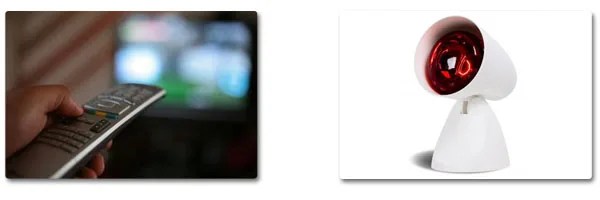

Infrared waves, or infrared light, are part of the electromagnetic spectrum. People encounter Infrared waves every day; the human eye cannot see it, but humans can detect it as heat.

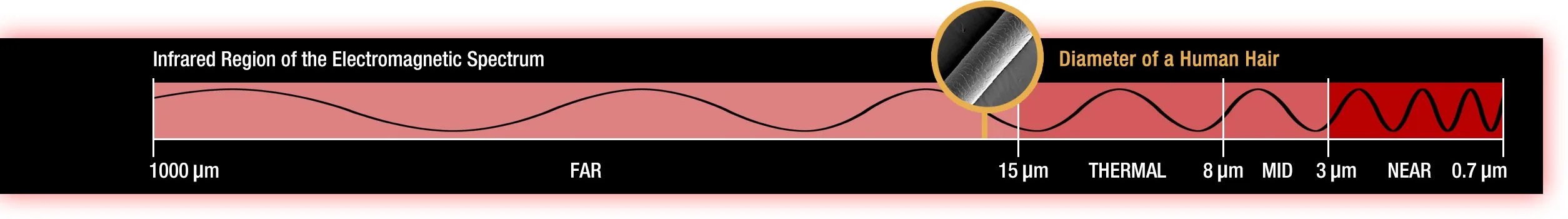

A remote control uses light waves just beyond the visible spectrum of light—infrared light waves—to change channels on your TV. This region of the spectrum is divided into near-, mid-, and far-infrared. The region from 8 to 15 microns (µm) is referred to by Earth scientists as thermal infrared since these wavelengths are best for studying the longwave thermal energy radiating from our planet.

DISCOVERY OF INFRARED

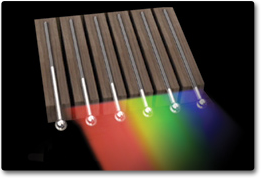

In 1800, William Herschel conducted an experiment measuring the difference in temperature between the colors in the visible spectrum. He placed thermometers within each color of the visible spectrum. The results showed an increase in temperature from blue to red. When he noticed an even warmer temperature measurement just beyond the red end of the visible spectrum, Herschel had discovered infrared light!

THERMAL IMAGING

We can sense some infrared energy as heat. Some objects are so hot they also emit visible light—such as a fire does. Other objects, such as humans, are not as hot and only emit only infrared waves. Our eyes cannot see these infrared waves but instruments that can sense infrared energy—such as night-vision goggles or infrared cameras–allow us to "see" the infrared waves emitting from warm objects such as humans and animals. The temperatures for the images below are in degrees Fahrenheit.

COOL ASTRONOMY

Many objects in the universe are too cool and faint to be detected in visible light but can be detected in the infrared. Scientists are beginning to unlock the mysteries of cooler objects across the universe such as planets, cool stars, nebulae, and many more, by studying the infrared waves they emit.

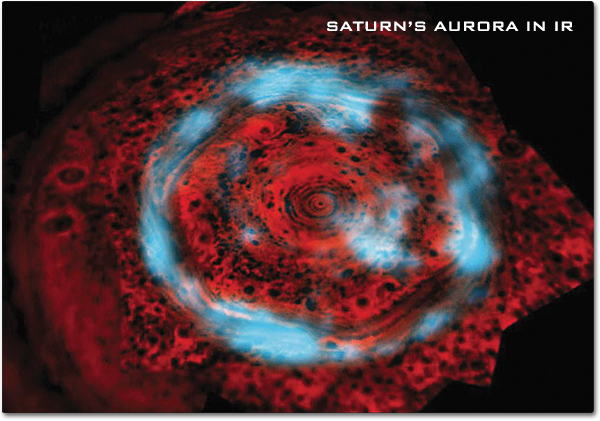

The Cassini spacecraft captured this image of Saturn's aurora using infrared waves. The aurora is shown in blue, and the underlying clouds are shown in red. These aurorae are unique because they can cover the entire pole, whereas aurorae around Earth and Jupiter are typically confined by magnetic fields to rings surrounding the magnetic poles. The large and variable nature of these aurorae indicates that charged particles streaming in from the Sun are experiencing some type of magnetism above Saturn that was previously unexpected.

SEEING THROUGH DUST

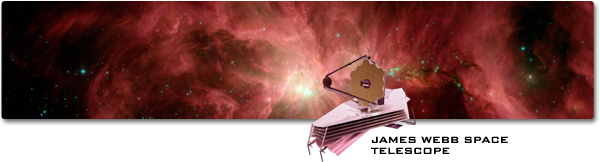

Infrared waves have longer wavelengths than visible light and can pass through dense regions of gas and dust in space with less scattering and absorption. Thus, infrared energy can also reveal objects in the universe that cannot be seen in visible light using optical telescopes. The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has three infrared instruments to help study the origins of the universe and the formation of galaxies, stars, and planets.

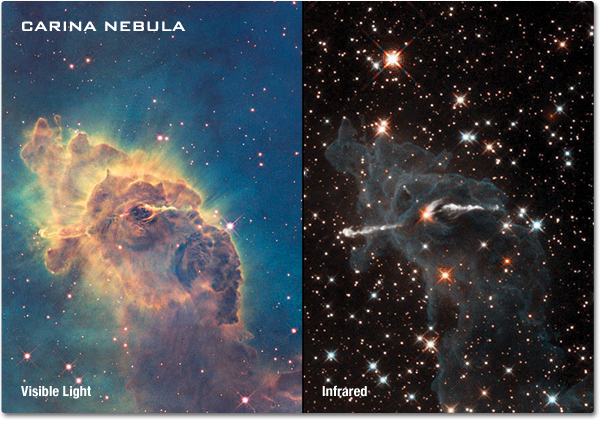

A pillar composed of gas and dust in the Carina Nebula is illuminated by the glow from nearby massive stars shown below in the visible light image from the Hubble Space Telescope. Intense radiation and fast streams of charged particles from these stars are causing new stars to form within the pillar. Most of the new stars cannot be seen in the visible-light image (left) because dense gas clouds block their light. However, when the pillar is viewed using the infrared portion of the spectrum (right), it practically disappears, revealing the baby stars behind the column of gas and dust.

MONITORING THE EARTH

To astrophysicists studying the universe, infrared sources such as planets are relatively cool compared to the energy emitted from hot stars and other celestial objects. Earth scientists study infrared as the thermal emission (or heat) from our planet. As incident solar radiation hits Earth, some of this energy is absorbed by the atmosphere and the surface, thereby warming the planet. This heat is emitted from Earth in the form of infrared radiation. Instruments onboard Earth observing satellites can sense this emitted infrared radiation and use the resulting measurements to study changes in land and sea surface temperatures.

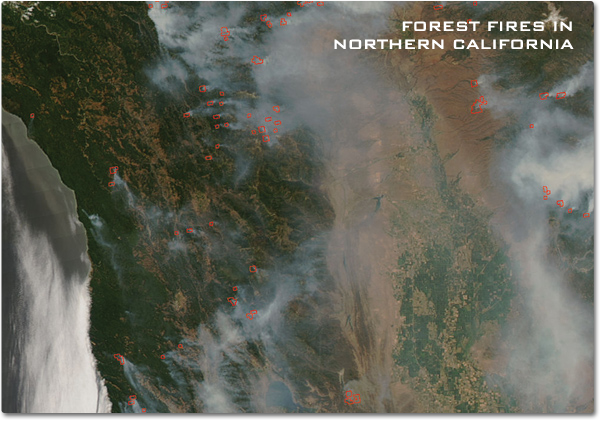

There are other sources of heat on the Earth's surface, such as lava flows and forest fires. The Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) instrument onboard the Aqua and Terra satellites uses infrared data to monitor smoke and pinpoint sources of forest fires. This information can be essential to firefighting efforts when fire reconnaissance planes are unable to fly through the thick smoke. Infrared data can also enable scientists to distinguish flaming fires from still-smoldering burn scars.

The global image on the right is an infrared image of the Earth taken by the GOES 6 satellite in 1986. A scientist used temperatures to determine which parts of the image were from clouds and which were land and sea. Based on these temperature differences, he colored each separately using 256 colors, giving the image a realistic appearance.

Why use the infrared to image the Earth? While it is easier to distinguish clouds from land in the visible range, there is more detail in the clouds in the infrared. This is great for studying cloud structure. For instance, note that darker clouds are warmer, while lighter clouds are cooler. Southeast of the Galapagos, just west of the coast of South America, there is a place where you can distinctly see multiple layers of clouds, with the warmer clouds at lower altitudes, closer to the ocean that's warming them.

We know, from looking at an infrared image of a cat, that many things emit infrared light. But many things also reflect infrared light, particularly near infrared light. Learn more about REFLECTED Near-infrared radiation.

Citation

APA

National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Science Mission Directorate. (2010). Infrared Waves. Retrieved [insert date - e.g. August 10, 2016], from NASA Science website: http://science.nasa.gov/ems/07_infraredwaves

MLA

Science Mission Directorate. "Infrared Waves" NASA Science. 2010. National Aeronautics and Space Administration. [insert date - e.g. 10 Aug. 2016] http://science.nasa.gov /ems/07_infraredwaves