4 min read

The glowing, clumpy streams of material shown in these NASA Hubble Space Telescope images are the signposts of star birth. Called Herbig-Haro or HH objects, these outflows speed along at over 440,000 miles an hour. When they "rear-end" slower gas, bow shocks (the blue features) arise as the material heats up. In HH 2 (lower right) several bow shocks (the compact blue and white features) occur where fast-moving clumps bunch up. In HH 34 (lower left) a grouping of merged bow shocks reveals regions that brighten and fade over time as the heated material cools, shown in red, where the shocks intersect. In HH 47 (top) a long jet of material has burst out of a dark cloud of gas and dust that hides the newly forming star. Credit: NASA/ESA/P. Hartigan (Rice University)

New movies created from years of still images collected by NASA's Hubble Space Telescope provide new details about the stellar birthing process, showing energetic jets of glowing gas ejected from young stars in unprecedented detail.

The jets are a byproduct of gas accretion around newly forming stars and shoot off at supersonic speeds of about 100 miles per second in opposite directions through space.

These phenomena are providing clues about the final stages of a star's birth, offering a peek at how our Sun came into existence 4.5 billion years ago.

Hubble's unique sharpness allows astronomers to see changes in the jets over just a few years' time. Most astronomical processes change over timescales that are much longer than a human lifetime.

A team of scientists led by astronomer Patrick Hartigan of Rice University in Houston, Texas, collected enough high-resolution Hubble images over a 14-year period to stitch together time-lapse movies of the jets ejected from three young stars.

NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope saw how a bright, clumpy jet called Herbig-Haro 34 (or HH 34) that was ejected from a young star has changed over time. Several bright regions in the lumpy gas signify where material is slamming into each other, heating up, and glowing. Red areas indicate where heated material cooled. Two regions at left, indicate fresh collision sites. A small knot of material within the blue feature (left) is either a new jet or magnetic energy being emitted by the star. Credit: NASA/ESA/P. Hartigan (Rice University)

Never-before-seen details in the jets' structure include knots of gas brightening and dimming over time and collisions between fast-moving and slow-moving material, creating glowing arrowhead features. The twin jets are not ejected in a steady stream, like water flowing from a garden hose. Instead, they are launched sporadically in clumps. The beaded-jet structure might be like a "ticker tape," recording how material episodically fell onto the star.

"For the first time we can actually observe how these jets interact with their surroundings by watching these time-lapse movies," said Hartigan. "Those interactions tell us how young stars influence the environments out of which they form. With movies like these, we can now compare observations of the jets with those produced by computer simulations and laboratory experiments to see what aspects of the interactions we understand and what parts we don't understand."

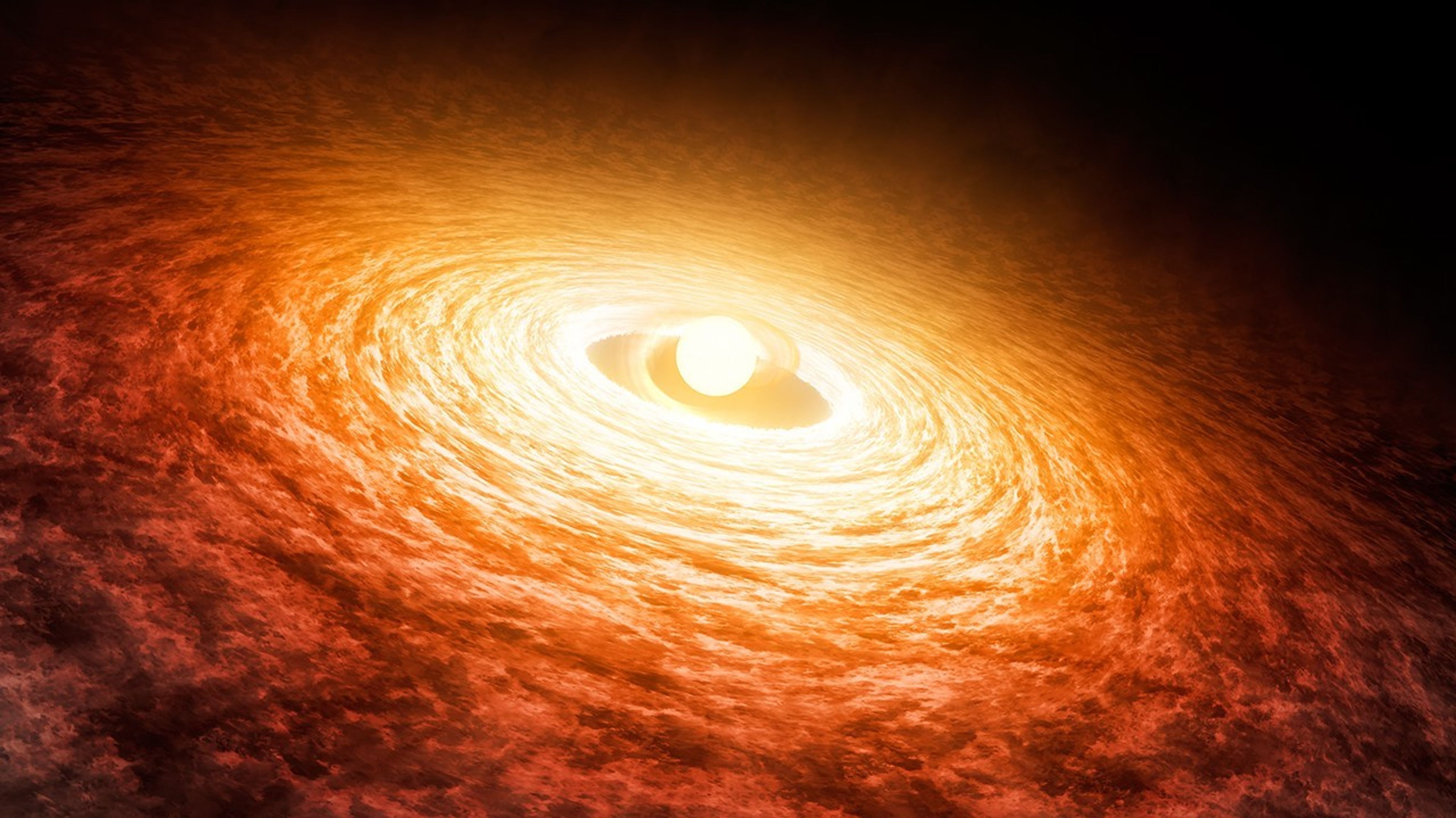

Jets are an active, short-lived phase of star formation, lasting only about 100,000 years. Astronomers don't know precisely what role jets play in the star-formation process or exactly how the star unleashes them. The jets appear to work in concert with magnetic fields. This helps bleed excess angular momentum from infalling material that is swirling rapidly. Once the material slows down it feeds the growing protostar, allowing it to fully condense into a mature star.

Hartigan and his colleagues used the Wide Field Planetary Camera 2 to study the jets, called Herbig-Haro (HH) objects, named in honor of George Herbig and Guillermo Haro, who studied the outflows in the 1950s. Hubble followed HH 1, HH 2, HH 34, HH 46, and HH 47 over three epochs, 1994, 1998, and 2008.

The team used computer software that wove together the observations to generate movies showing continuous motion.

"Taken together, our results paint a picture of jets as remarkably diverse objects that undergo highly structured interactions both within the material in the outflow and between the jet and the surrounding gas," Hartigan explained. "This contrasts with the bulk of the existing simulations, many of which depict jets as smooth systems."

Hartigan's team's results appeared in the July 20, 2011 issue of The Astrophysical Journal.

For images and more information about these results, visit:

Ray Villard

Space Science Telescope Institute