5 min read

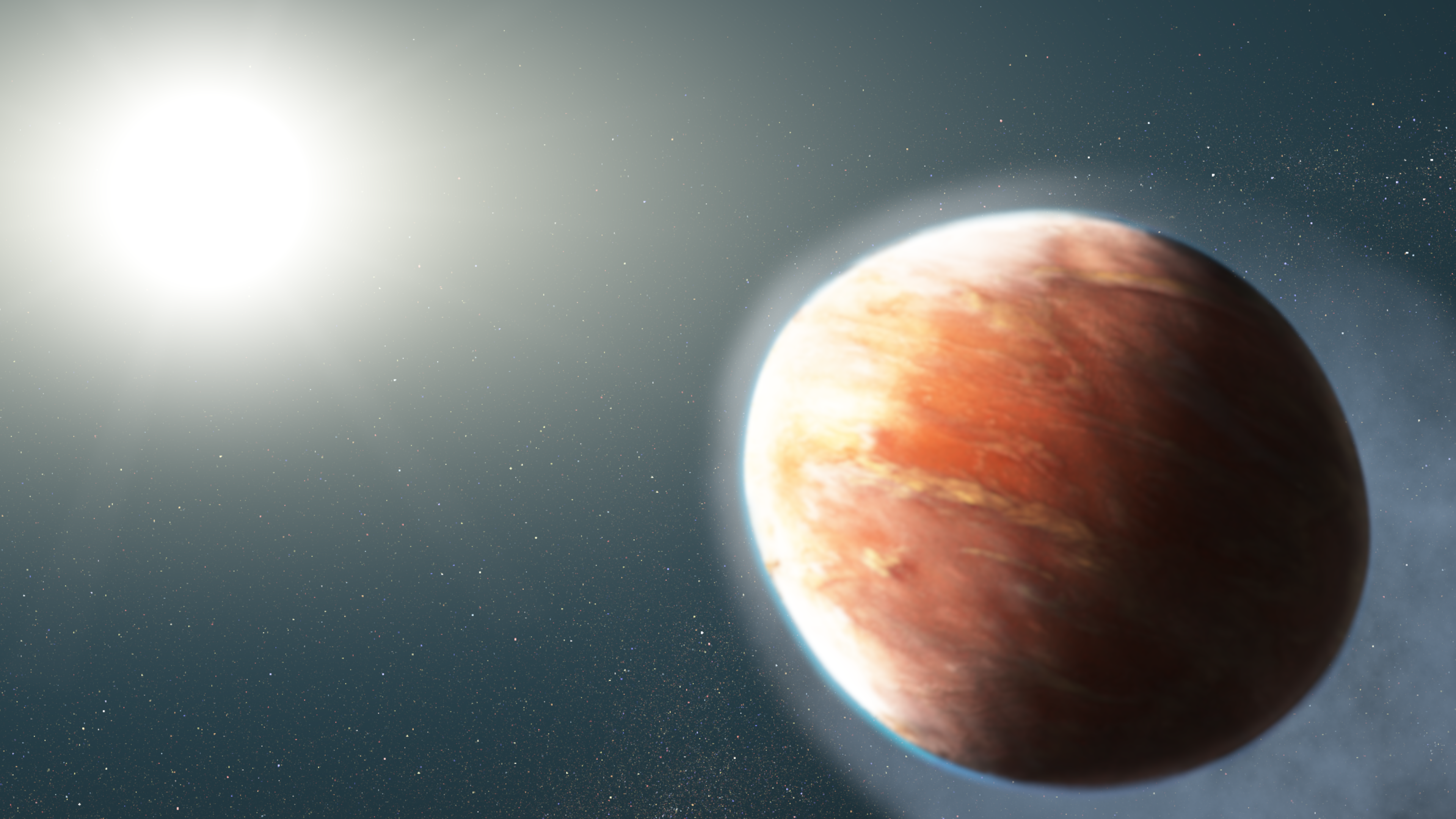

How can a planet be "hotter than hot?" The answer is when heavy metals are detected escaping from the planet's atmosphere, instead of condensing into clouds.

Observations by NASA's Hubble Space Telescope reveal magnesium and iron gas streaming from the strange world outside our solar system known as WASP-121b. The observations represent the first time that so-called "heavy metals"—elements heavier than hydrogen and helium—have been spotted escaping from a hot Jupiter, a large, gaseous exoplanet very close to its star.

Normally, hot Jupiter-sized planets are still cool enough inside to condense heavier elements such as magnesium and iron into clouds.

But that's not the case with WASP-121b, which is orbiting so dangerously close to its star that its upper atmosphere reaches a blazing 4,600 degrees Fahrenheit. The WASP-121 system resides about 900 light-years from Earth.

"Heavy metals have been seen in other hot Jupiters before, but only in the lower atmosphere," explained lead researcher David Sing of the Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland. "So you don't know if they are escaping or not. With WASP-121b, we see magnesium and iron gas so far away from the planet that they're not gravitationally bound."

Ultraviolet light from the host star, which is brighter and hotter than the Sun, heats the upper atmosphere and helps lead to its escape. In addition, the escaping magnesium and iron gas may contribute to the temperature spike, Sing said. "These metals will make the atmosphere more opaque in the ultraviolet, which could be contributing to the heating of the upper atmosphere," he explained.

The sizzling planet is so close to its star that it is on the cusp of being ripped apart by the star's gravity. This hugging distance means that the planet is football shaped due to gravitational tidal forces.

"We picked this planet because it is so extreme," Sing said. "We thought we had a chance of seeing heavier elements escaping. It's so hot and so favorable to observe, it's the best shot at finding the presence of heavy metals. We were mainly looking for magnesium, but there have been hints of iron in the atmospheres of other exoplanets. It was a surprise, though, to see it so clearly in the data and at such great altitudes so far away from the planet. The heavy metals are escaping partly because the planet is so big and puffy that its gravity is relatively weak. This is a planet being actively stripped of its atmosphere."

The researchers used the observatory's Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph to search in ultraviolet light for the spectral signatures of magnesium and iron imprinted on starlight filtering through WASP-121b's atmosphere as the planet passed in front of, or transited, the face of its home star.

This exoplanet is also a perfect target for NASA's upcoming James Webb Space Telescope to search in infrared light for water and carbon dioxide, which can be detected at longer, redder wavelengths. The combination of Hubble and Webb observations would give astronomers a more complete inventory of the chemical elements that make up the planet's atmosphere.

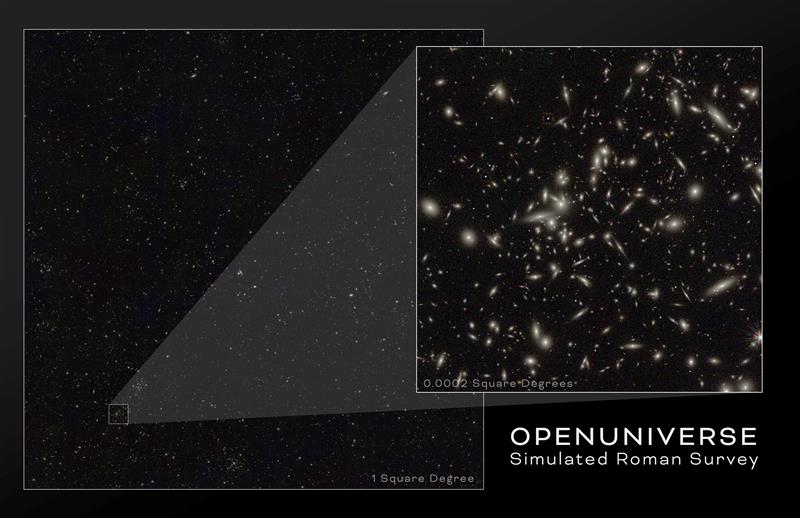

The WASP-121b study is part of the Panchromatic Comparative Exoplanet Treasury (PanCET) survey, a Hubble program to look at 20 exoplanets, ranging in size from super-Earths (several times Earth's mass) to Jupiters (which are over 100 times Earth's mass), in the first large-scale ultraviolet, visible, and infrared comparative study of distant worlds.

The observations of WASP-121b add to the developing story of how planets lose their primordial atmospheres. When planets form, they gather an atmosphere containing gas from the disk in which the planet and star formed. These atmospheres consist mostly of the primordial, lighter-weight gases hydrogen and helium, the most plentiful elements in the universe. This atmosphere dissipates as a planet moves closer to its star.

"The hot Jupiters are mostly made of hydrogen, and Hubble is very sensitive to hydrogen, so we know these planets can lose the gas relatively easily," Sing said. "But in the case of WASP-121b, the hydrogen and helium gas is outflowing, almost like a river, and is dragging these metals with them. It's a very efficient mechanism for mass loss."

The results will appear online today in The Astronomical Journal.

The Hubble Space Telescope is a project of international cooperation between NASA and ESA (European Space Agency). NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, manages the telescope. The Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) in Baltimore, Maryland, conducts Hubble science operations. STScI is operated for NASA by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy in Washington, D.C.

Claire Andreoli

NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Maryland

301-286-1940

claire.andreoli@nasa.gov

Donna Weaver / Ray Villard

Space Telescope Science Institute, Baltimore, Maryland

410-338-4493 / 410-338-4514

dweaver@stsci.edu / villard@stsci.edu

David Sing

Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland

dsing@jhu.edu