6 min read

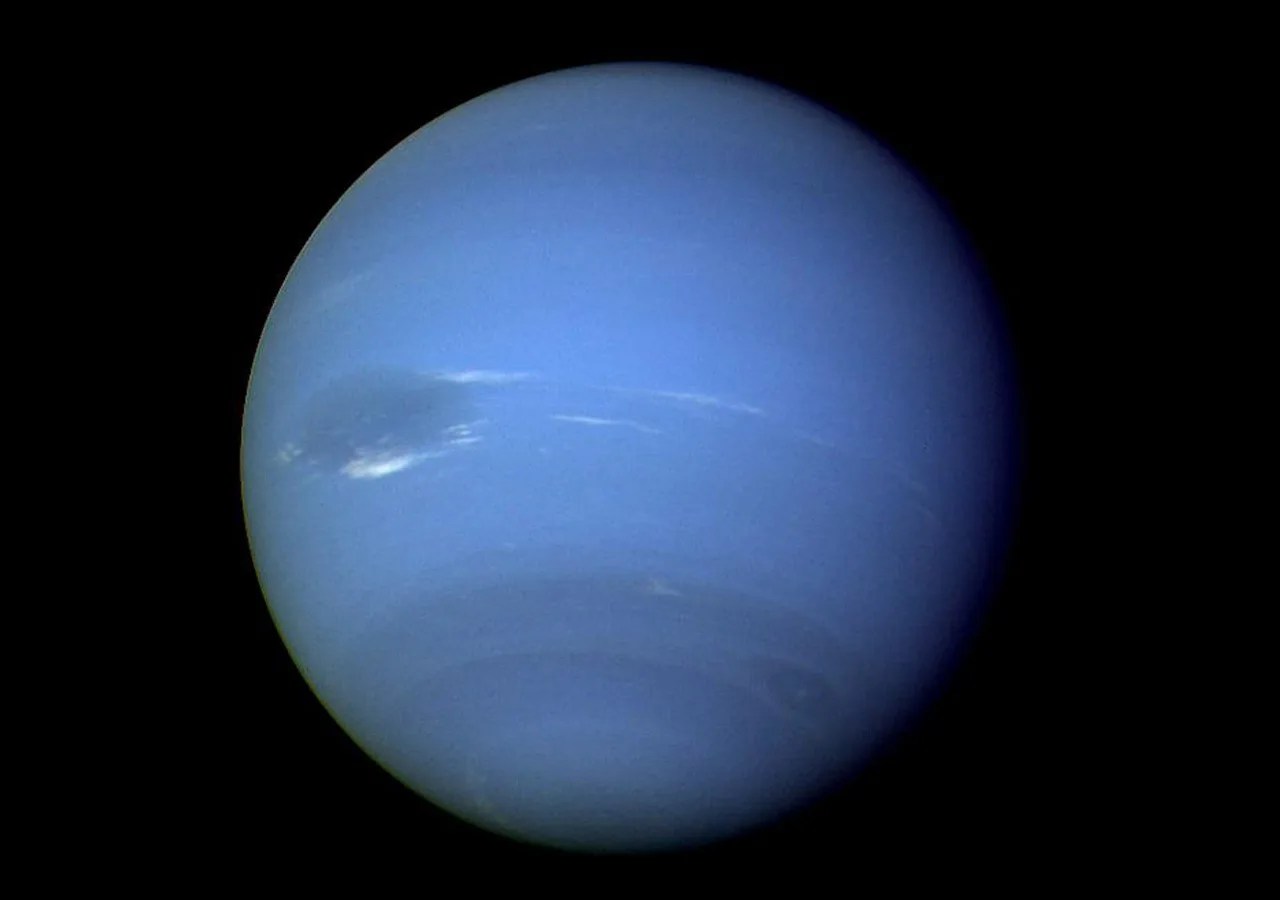

Astronomers have uncovered a link between Neptune's shifting cloud abundance and the 11-year solar cycle, in which the waxing and waning of the Sun's entangled magnetic fields drives solar activity.

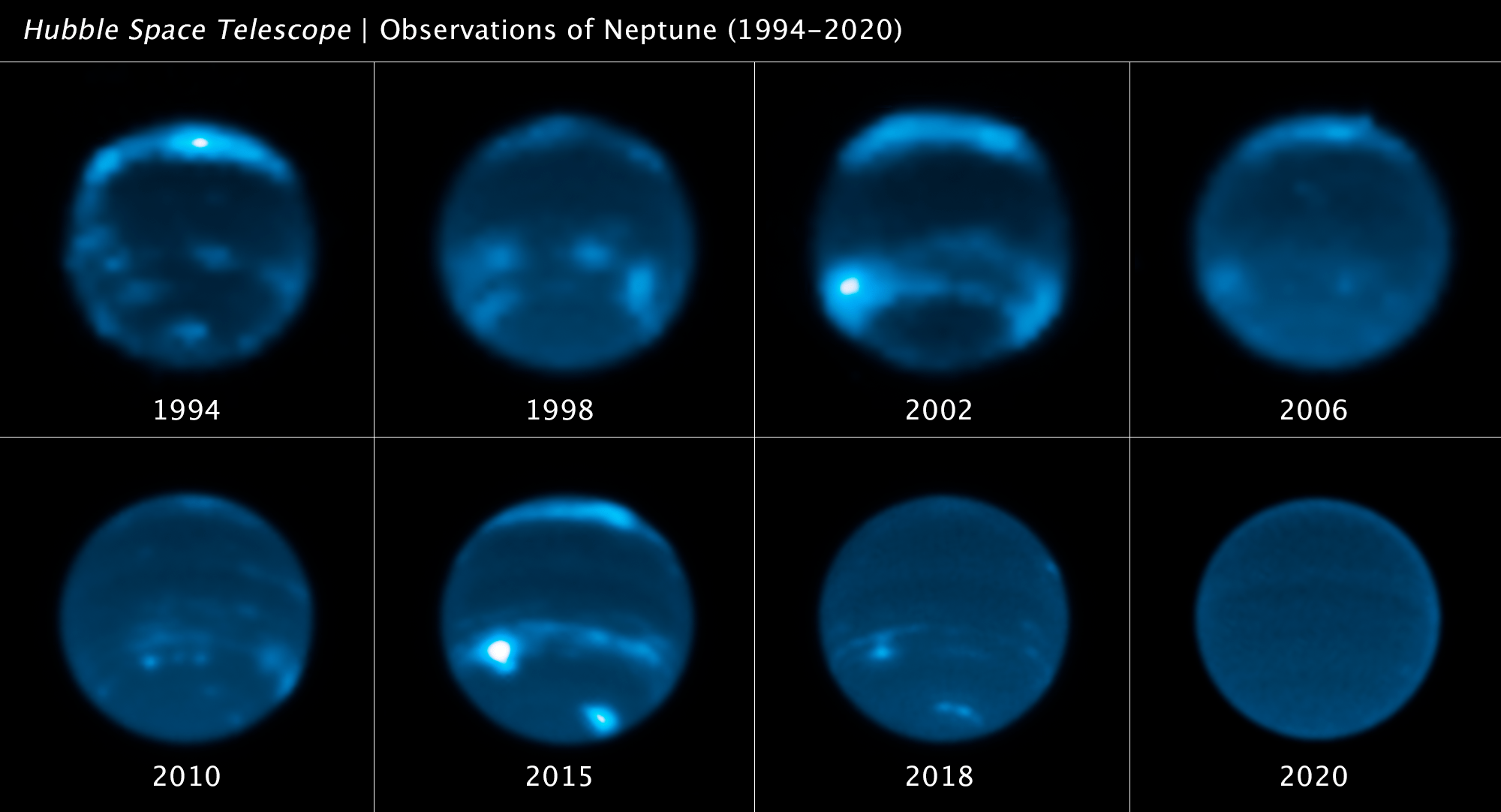

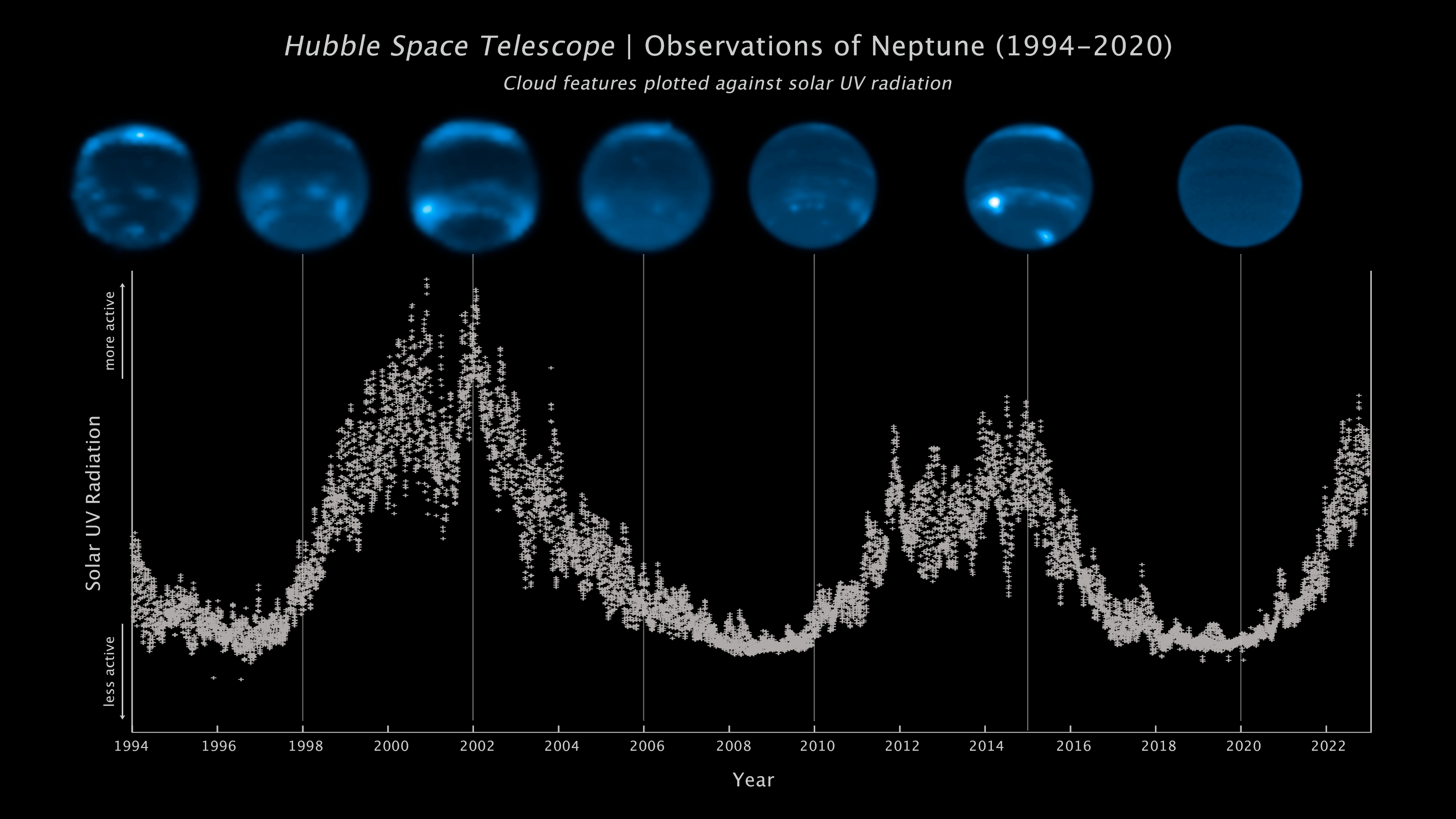

This discovery is based on three decades of Neptune observations captured by NASA's Hubble Space Telescope and the W. M. Keck Observatory in Hawaii, as well as data from the Lick Observatory in California.

The link between Neptune and solar activity is surprising to planetary scientists because Neptune is our solar system's farthest major planet and receives sunlight with about 0.1% of the intensity Earth receives. Yet Neptune's global cloudy weather seems to be driven by solar activity, and not the planet's four seasons, which each last approximately 40 years.

At present, the cloud coverage seen on Neptune is extremely low, with the exception of some clouds hovering over the giant planet's south pole. A University of California (UC) Berkeley-led team of astronomers discovered that the abundance of clouds normally seen at the icy giant's mid-latitudes started to fade in 2019.

"I was surprised by how quickly clouds disappeared on Neptune," said Imke de Pater, emeritus professor of astronomy at UC Berkeley and senior author of the study. "We essentially saw cloud activity drop within a few months," she said.

"Even now, four years later, the most recent images we took this past June still show the clouds haven't returned to their former levels," said Erandi Chavez, a graduate student at the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard-Smithsonian (CfA) in Cambridge, Massachusetts, who led the study when she was an undergraduate astronomy student at UC Berkeley. "This is extremely exciting and unexpected, especially since Neptune's previous period of low cloud activity was not nearly as dramatic and prolonged."

To monitor the evolution of Neptune's appearance, Chavez and her team analyzed Keck Observatory images taken from 2002 to 2022, the Hubble Space Telescope archival observations beginning in 1994, and data from the Lick Observatory in California from 2018 to 2019.

In recent years, the Keck observations have been complemented by images taken as part of the Twilight Zone program and by Hubble's Outer Planet Atmospheres Legacy (OPAL) program.

The images reveal an intriguing pattern between seasonal changes in Neptune’s cloud cover and the solar cycle – the period when the Sun's magnetic field flips every 11 years as it becomes more tangled like a ball of yarn. This is evident in the increasing number of sunspots and increasing solar flare activity. As the cycle progresses, the Sun’s tempestuous behavior builds to a maximum, until the magnetic field beaks down and reverses polarity. Then the Sun settles back down to a minimum, only to start another cycle.

When it's stormy weather on the Sun, more intense ultraviolet (UV) radiation floods the solar system. The team found that two years after the solar cycle's peak, an increasing number of clouds appear on Neptune. The team further found a positive correlation between the number of clouds and the ice giant's brightness from the sunlight reflecting off it.

"These remarkable data give us the strongest evidence yet that Neptune's cloud cover correlates with the Sun’s cycle," said de Pater. "Our findings support the theory that the Sun's UV rays, when strong enough, may be triggering a photochemical reaction that produces Neptune’s clouds."

Scientists discovered the connection between the solar cycle and Neptune's cloudy weather pattern by looking at 2.5 cycles of cloud activity recorded over the 29-year span of Neptunian observations. During this time, the planet's reflectivity increased in 2002 then dimmed in 2007. Neptune became bright again in 2015, then darkened in 2020 to the lowest level ever observed, which is when most of the clouds went away.

The changes in Neptune's brightness caused by the Sun appear to go up and down relatively in sync with the coming and going of clouds on the planet. However there is a two-year time lag between the peak of the solar cycle and the abundance of clouds seen on Neptune. The chemical changes are caused by photochemistry, which happens high in Neptune's upper atmosphere and takes time to form clouds.

"It's fascinating to be able to use telescopes on Earth to study the climate of a world more than 2.5 billion miles away from us," said Carlos Alvarez, staff astronomer at Keck Observatory and co-author of the study. "Advances in technology and observations have enabled us to constrain Neptune's atmospheric models, which are key to understanding the correlation between the ice giant's climate and the solar cycle."

However, more work is necessary. For example, while an increase in UV sunlight could produce more clouds and haze, it could also darken them, thereby reducing Neptune's overall brightness. Storms on Neptune rising up from the deep atmosphere affect the cloud cover, but are not related to photochemically produced clouds, and hence may complicate correlation studies with the solar cycle. Continued observations of Neptune are also needed to see how long the current near-absence of clouds will last.

The research team continues to track Neptune's cloud activity. "We have seen more clouds in the most recent Keck images that were taken during the same time NASA's James Webb Space Telescope observed the planet; these clouds were in particular seen at northern latitudes and at high altitudes, as expected from the observed increase in the solar UV flux over the past approximately 2 years," said de Pater.

The combined data from Hubble, the Webb Space Telescope, Keck Observatory, and the Lick Observatory will enable further investigations into the physics and chemistry that lead to Neptune's dynamic appearance, which in turn may help deepen astronomers' understanding not only of Neptune, but also of exoplanets, since many of the planets beyond our solar system are thought to have Neptune-like qualities.

The Hubble Space Telescope is a project of international cooperation between NASA and ESA. NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, manages the telescope. The Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) in Baltimore conducts Hubble science operations. STScI is operated for NASA by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy, in Washington, D.C.

Claire Andreoli

NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, MD

claire.andreoli@nasa.gov

Robert Garner

NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, MD

rob.garner@nasa.gov

Ray Villard

Space Telescope Science Institute, Baltimore, MD

villard@stsci.edu

Mari-Ela Chock

W. M. Keck Observatory, Mauna Kea, HI

mchock@keck.hawaii.edu

Robert Sanders

University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, CA

rlsanders@berkeley.edu