What is the Late Heavy Bombardment?

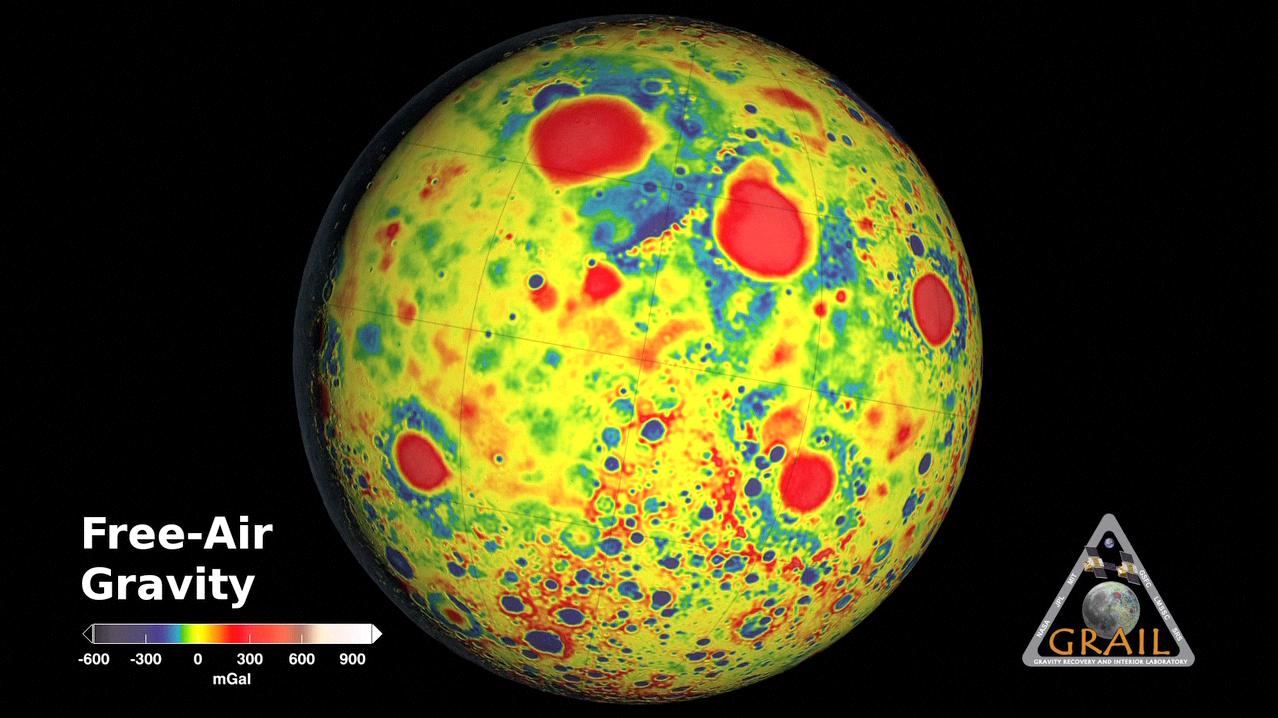

Around 4 billion years ago, our young inner solar system underwent a cataclysmic pummeling by asteroids that carved huge basins into Earth’s Moon. That’s the theory of the Late Heavy Bombardment, which posits that a sudden change in the orbits of the giant planets ― Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune ― threw the asteroid belt into disarray and sent those leftover pieces of the solar system’s formation crashing into the inner planets.

When astronauts visited the Moon, they brought back rock samples containing impact melt, a type of rock that only forms when material melts instantaneously upon being struck by an impactor. Scientists found that many of the samples, despite coming from different locations on the near side of the Moon, had similar ages of roughly 4 billion years, with very few samples showing older impacts. This potentially indicated a period of increased and dramatic collisions in the solar system.

The idea was and remains fairly controversial. Some argued that the samples came from too small an area (only about 4 percent of the Moon) to be conclusive. Perhaps they were all affected by the same impact or a few impacts. But samples of lunar meteorites that fell to Earth were found to follow the same pattern.

On Earth, most evidence of even such an intense bombardment would have been destroyed by erosion and plate tectonics, but signs like geological layers of small beads called spherules, created when droplets of molten and vaporized rock condensed and fell back to Earth, have been discovered that date back to about 3.5 billion years.

The Late Heavy Bombardment isn’t a done deal. As more studies were done, scientists realized that lunar basins were extremely difficult to date and could be contaminated with material from the impacts that formed other basins. More precise measurements of the Apollo samples over time found tiny portions of rock that were older than 4 billion years. Scientists argued that the timelines for the way the bombardment would have affected Earth didn’t match up with other studies and theories about when water and life took hold on the planet.

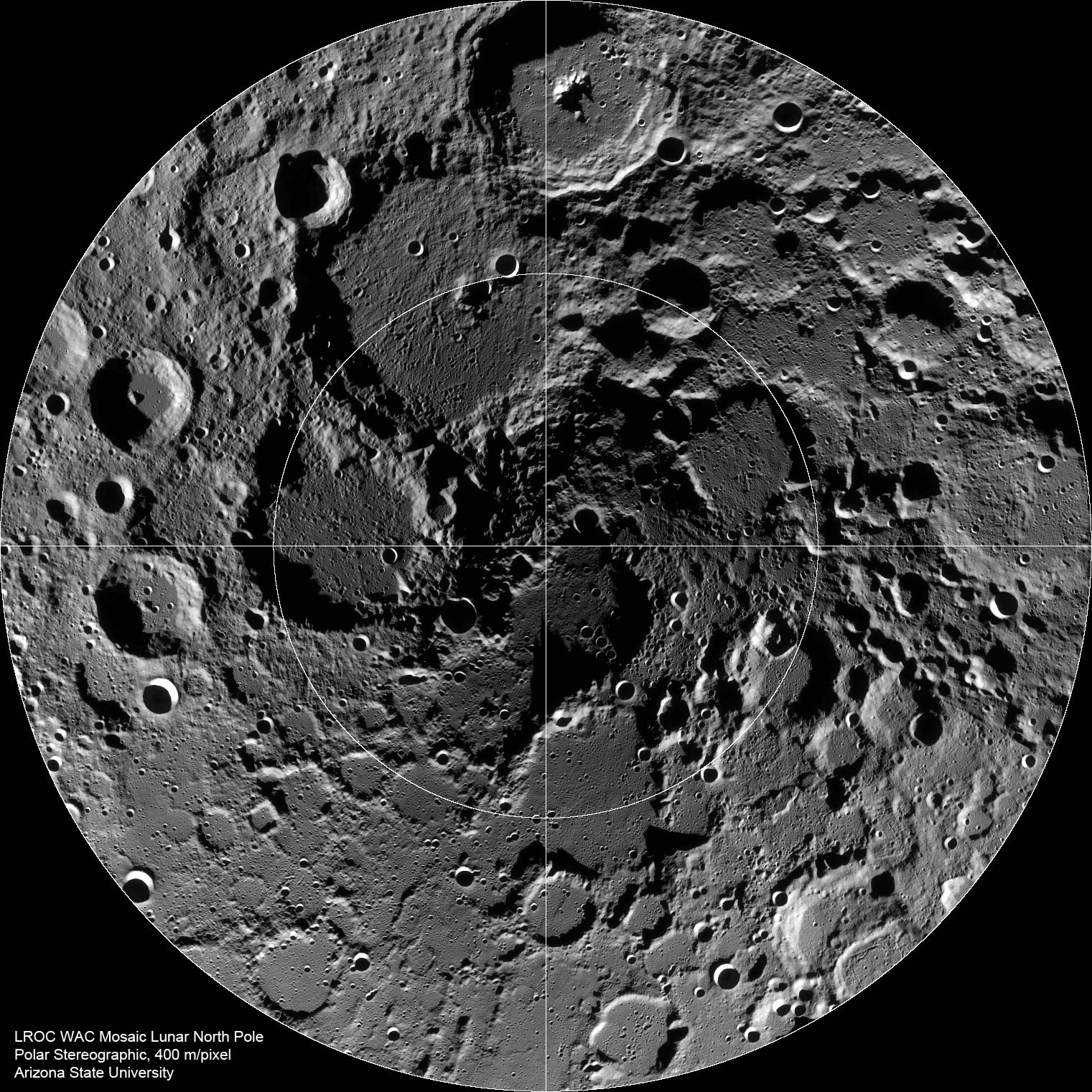

The debate continues today, with scientists proposing that the Late Heavy Bombardment was more gradual, broken into segments, or that such a spike didn’t occur at all. A decisive answer could be provided by future lunar missions that return samples from other locations on the Moon, especially the large basins such as the South-Pole Aitken basin. Such samples could show that the evidence of impacts after 4 billion years ― but not before ― is consistent over the lunar surface. Or they could show that the Late Heavy Bombardment was no more than an illusion caused by incomplete data.

Writer: Tracy Vogel; Science Advisors: Daniel P. Moriarty (University of Maryland at College Park), Natalie M. Curran (NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center)

All About Lunar Craters

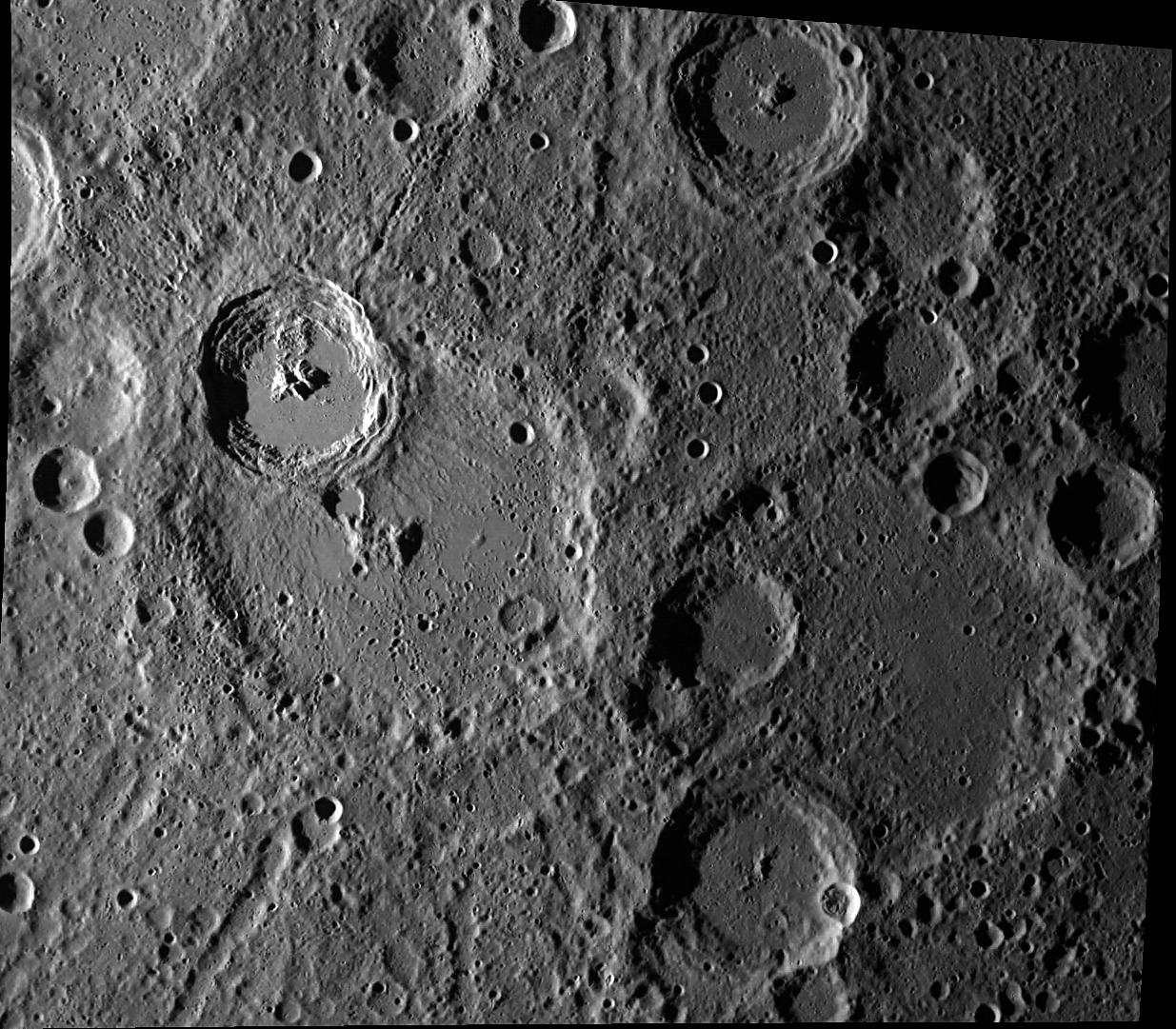

Craters are the mark the passing universe leaves on the Moon, a cosmic guestbook. They tell us the history not only of the Moon, but of our solar system.

Learn More

Explore Further

Expand your knowledge about lunar craters.

What is the Late Heavy Bombardment?

Lunar craters give scientists a peek into our solar system’s asteroid-pummeled past.

The Explosive History of Orientale Basin

The Moon’s Orientale basin demonstrates the violence of a tremendous lunar impact.