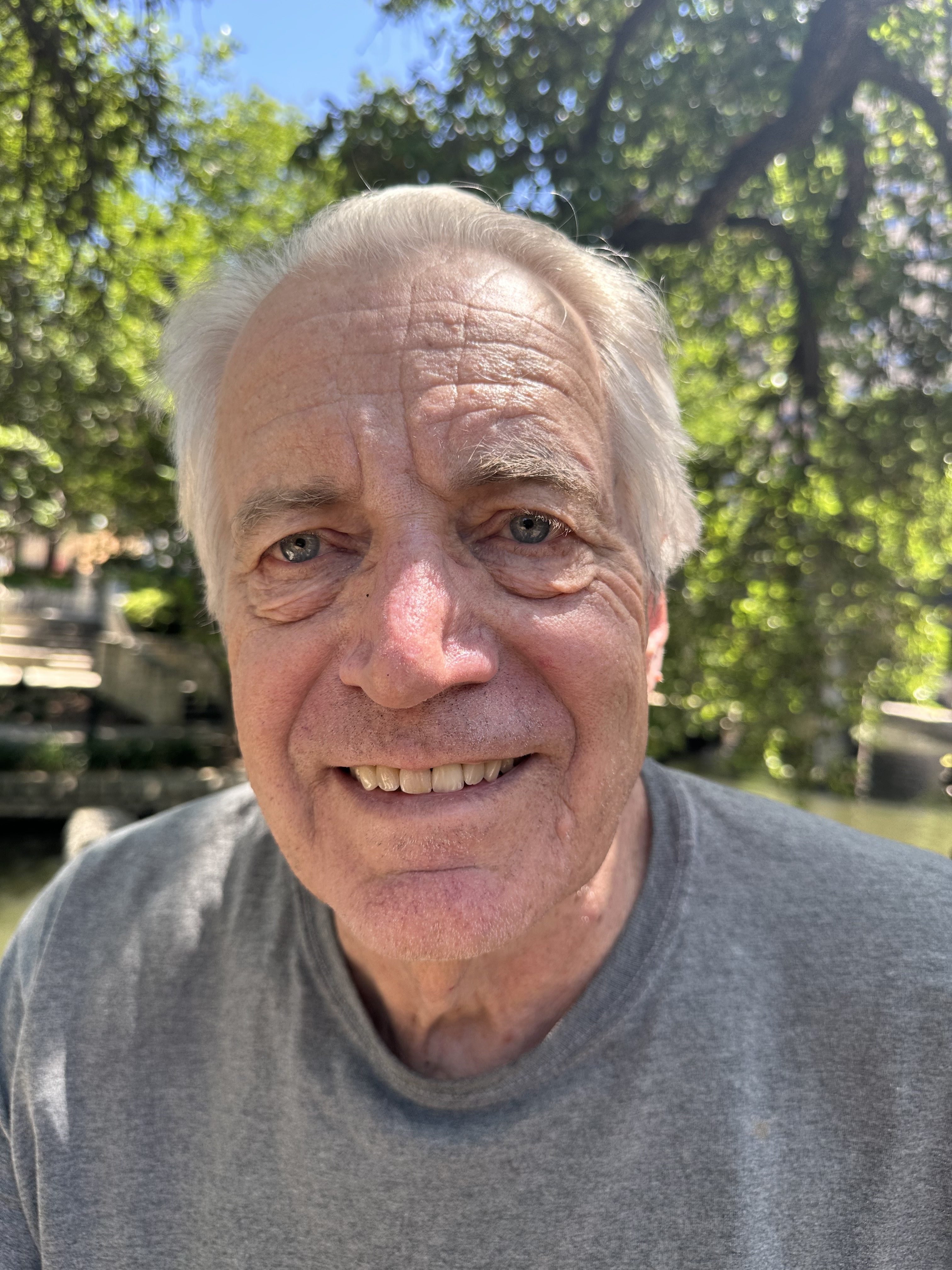

Gordon Johnston

Program Executive (Retired) | NASA Headquarters

Gordon is enjoying retirement after more than 40 years in the space business, but he still shares his expertise as a volunteer writer of a monthly NASA skywatching guide. His work at NASA spanned the first Mars landings of the 1970s to OSIRIS-REx, NASA's first asteroid sample return mission. Gordon also plays the fiddle in a traditional Irish band.

I was born and raised in the Los Angeles area, near the coast. My father was an aeronautical engineer at the Rand Corp. in Santa Monica, Calif. My mother worked as a secretary.

I vaguely remember my father taking me outside to watch one of the first satellites pass overhead. It was probably Echo, but I think I was far too young to figure out what he was pointing at.

I guess I got hooked on space through science fiction. One early book that made an impression on me was "The Forgotten Door" by Alexander Key. The main character comes from a time or place far more advanced than Earth in the present day. From the book I took away a vision of the future where technology made life simpler and happier rather than just busier and more complicated. At one point I read the whole science fiction section at my local library, reading my way across every shelf.

Several books by Arthur C. Clarke made an impression on me, including "The Deep Range" and "The City and the Stars." What I liked about "The Deep Range" is that it was about using the skills we learn in space to explore our oceans and feed the planet.

It was a lucky break. I was working on my master's degree in mathematics, and I wanted to do space-related work. (I had applied to NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, but had yet to hear from them.) One day while looking through the Los Angeles Times I came across a want ad for mathematicians, which turned out to be for a contractor job at JPL working on the Viking 1 mission to Mars. I applied, interviewed and got the job. JPL liked my work, and when the Galileo mission to Jupiter got its new start a year later, JPL hired me as a permanent employee working half time on Viking and half time on Galileo.

I would have to say first my father and second, the writings of Arthur C. Clarke.

My father was a competent engineer; he knew how to make things work. My father was also an airplane enthusiast. His hobby was to build accurate scale replicas of World War I aircraft. These replicas had gas engines and flew, controlled by "U-control" wires. I grew up helping him build, fly and repair these models.

Most Americans believe in the future, that the world we leave our children can be better than the world today; that it is our duty to work to make this true. Arthur C. Clarke wrote "The Deep Range" in 1957 when the world's population was approaching 3 billion. In this book he speculated that as the world's population grew to 6 billion, we would have to expand and farm the algae fields of our oceans in much the same way we have expanded and farm the grasslands on our continents. Today the world's population is over seven billion, and the UN medium projection is that we will peak at over 9 billion people later in this century. It is too late, and there are too many of us to go "back to nature," at least for the foreseeable future. But what we can do is use technology, including space technology, wisely and sustainably to gain the knowledge and capabilities to give all of us on Earth the opportunity to live rich and fulfilling lives.

The program executive monitors the engineering part of a three-person team at NASA headquarters who monitor the development of robotic space missions. A program scientist makes sure the mission will achieve its science goals and the resource analyst manages the money and congressional reporting requirements.

I have the most fun when I am learning new things or working with a team of dedicated people to understand a challenging problem or to assess widely varying technical options. I enjoy it when we turn a problem around, look at it in a new way and come up with approaches to solutions that were not obvious before.

Often in my line of work it can be years between when I work on technology or assess a mission option and when that technology or mission starts returning real science from space. Several of the instrument technologies I helped sponsor are now operating in space. When I worked in Earth Science I led the evaluation of several mission proposals, three of which are still operating (GRACE, CloudSat and CALIPSO). I feel a quiet sense of satisfaction when I see the new knowledge and useful results that come from things I helped make happen.

Look for a career, not just a job. Seek out work that you enjoy and believe in. This makes it far easier for you to get excited about and involved in the work you do, as well as be able to put in the extra effort needed to do well. A technical education is important, although it can be in any of a number of fields, as the main skill needed is the ability to understand complex problems and work them through to real solutions.

I enjoy spending time outdoors. I also enjoy music. When I moved to the Washington, D.C. area I met people who play traditional Irish music, so I have taken up the fiddle.