5 min read

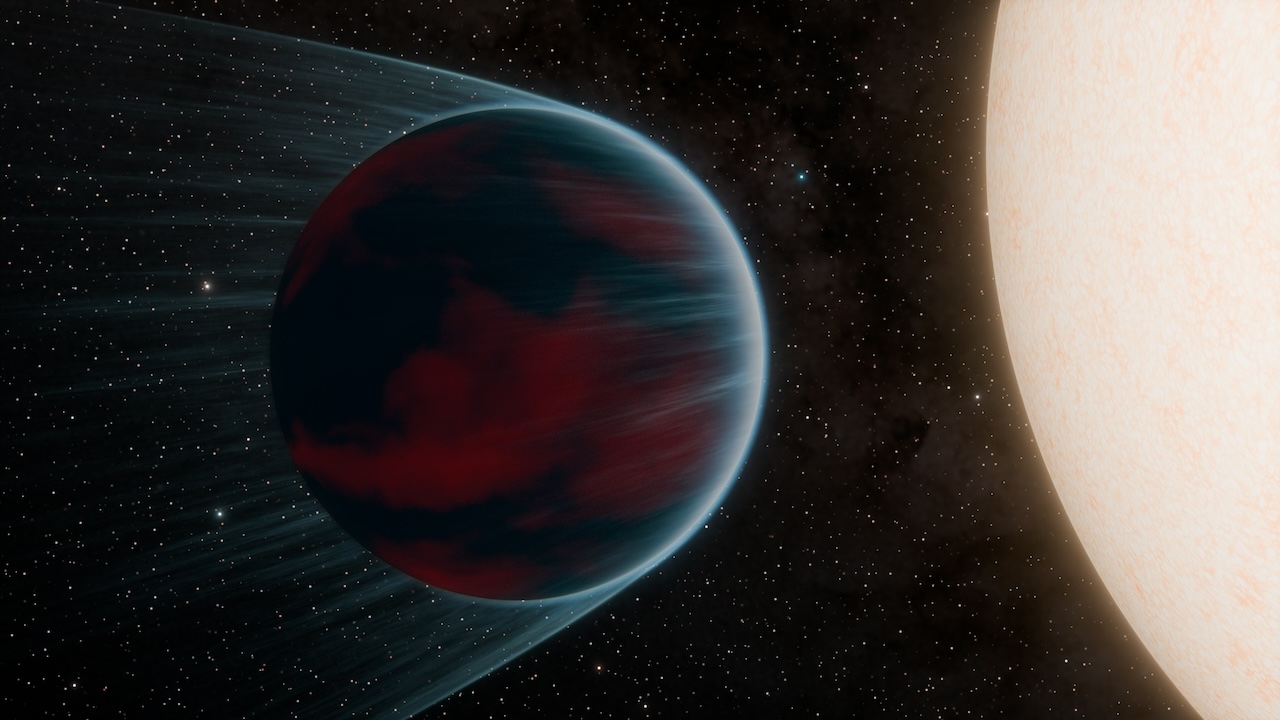

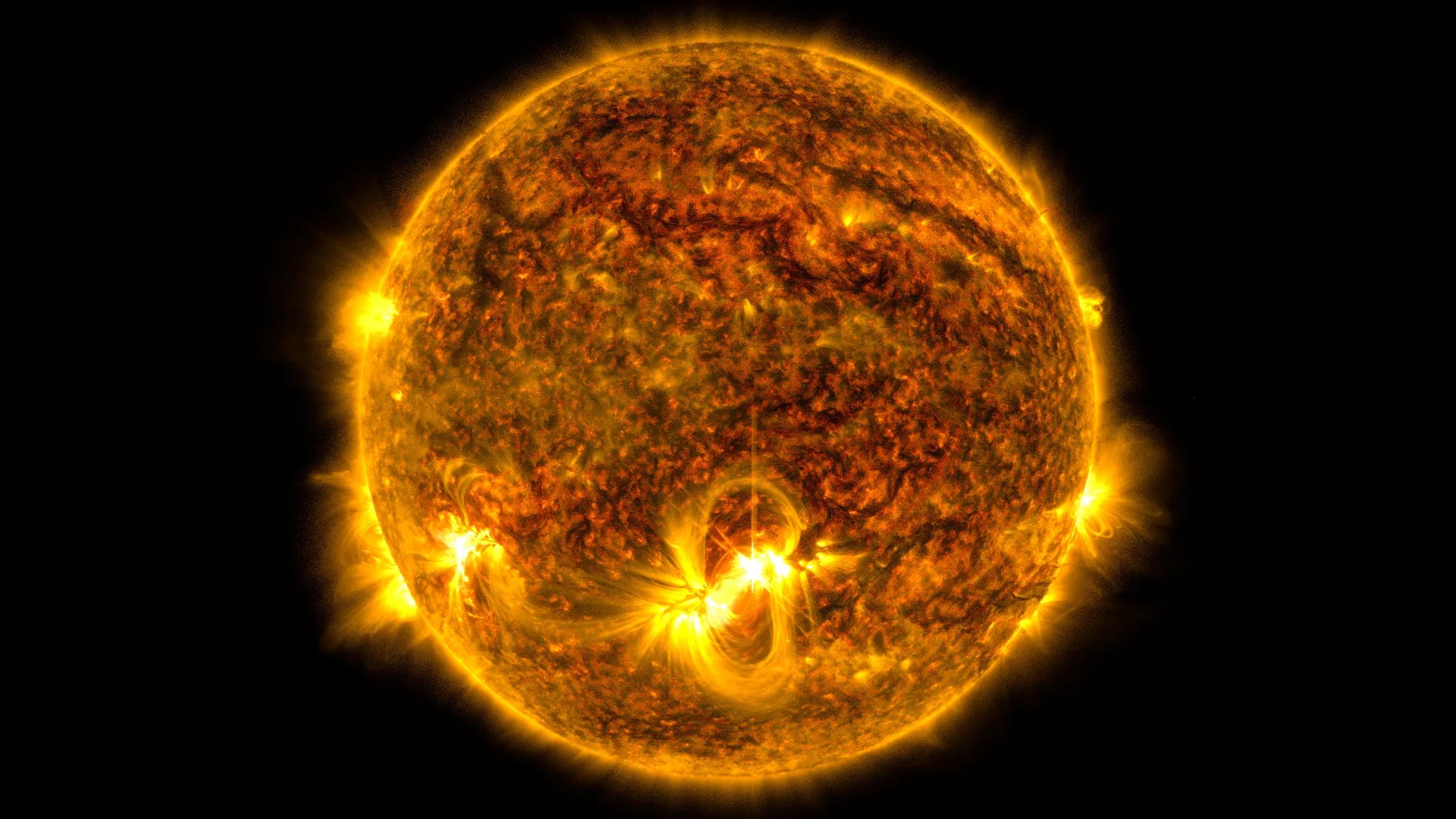

If we want to know more about whether life could survive on a planet outside our solar system, it’s important to know the age of its star. Young stars have frequent releases of high-energy radiation called flares that can zap their planets' surfaces. If the planets are newly formed, their orbits may also be unstable. On the other hand, planets orbiting older stars have survived the spate of youthful flares, but have also been exposed to the ravages of stellar radiation for a longer period of time.

Scientists now have a good estimate for the age of one of the most intriguing planetary systems discovered to date– TRAPPIST-1, a system of seven Earth-size worlds orbiting an ultra-cool dwarf star about 40 light-years away. Researchers say in a new study that the TRAPPIST-1 star is quite old: between 5.4 and 9.8 billion years. This is up to twice as old as our own solar system, which formed some 4.5 billion years ago.

If there is life on these planets, I would speculate that it has to be hardy life, because it has to be able to survive some potentially dire scenarios for billions of years.

Adam Burgasser

University of California, San Diego

The seven wonders of TRAPPIST-1 were revealed earlier this year in a NASA news conference, using a combination of results from the Transiting Planets and Planetesimals Small Telescope (TRAPPIST) in Chile, NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope, and other ground-based telescopes. Three of the TRAPPIST-1 planets reside in the star’s "habitable zone," the orbital distance where a rocky planet with an atmosphere could have liquid water on its surface. All seven planets are likely tidally locked to their star, each with a perpetual dayside and nightside.

At the time of its discovery, scientists believed the TRAPPIST-1 system had to be at least 500 million years old, since it takes stars of TRAPPIST-1’s low mass (roughly 8 percent that of the Sun) roughly that long to contract to its minimum size, just a bit larger than the planet Jupiter. However, even this lower age limit was uncertain; in theory, the star could be almost as old as the universe itself. Are the orbits of this compact system of planets stable? Might life have enough time to evolve on any of these worlds?

"Our results really help constrain the evolution of the TRAPPIST-1 system, because the system has to have persisted for billions of years. This means the planets had to evolve together, otherwise the system would have fallen apart long ago," said Adam Burgasser, an astronomer at the University of California, San Diego, and the paper's first author. Burgasser teamed up with Eric Mamajek, deputy program scientist for NASA's Exoplanet Exploration Program based at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, California, to calculate TRAPPIST-1's age. Their results will be published in The Astrophysical Journal.

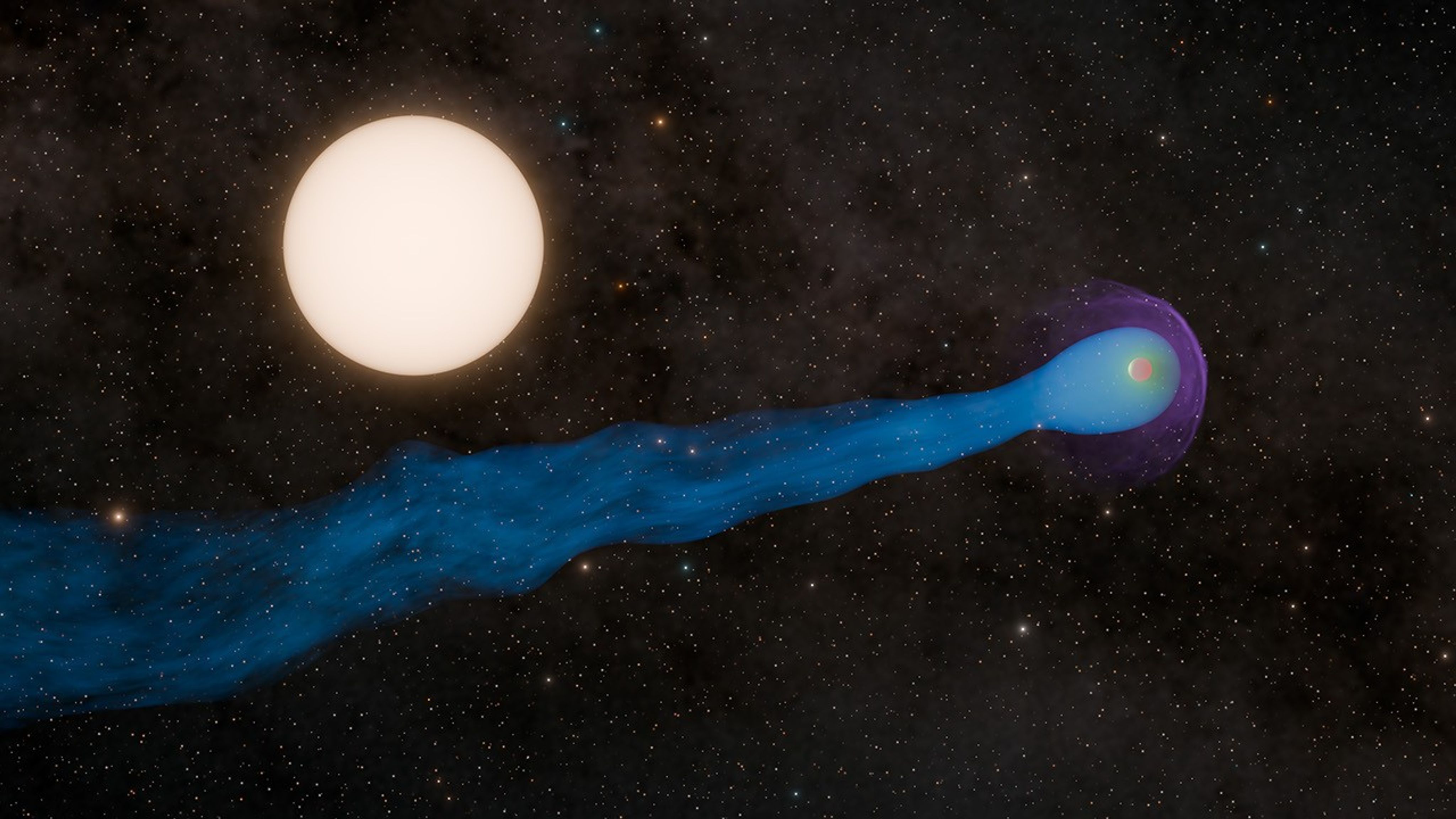

It is unclear what this older age means for the planets' habitability. On the one hand, older stars flare less than younger stars, and Burgasser and Mamajek confirmed that TRAPPIST-1 is relatively quiet compared to other ultra-cool dwarf stars. On the other hand, since the planets are so close to the star, they have soaked up billions of years of high-energy radiation, which could have boiled off atmospheres and large amounts of water. In fact, the equivalent of an Earth ocean may have evaporated from each TRAPPIST-1 planet except for the two most distant from the host star: planets g and h. In our own solar system, Mars is an example of a planet that likely had liquid water on its surface in the past, but lost most of its water and atmosphere to the Sun’s high-energy radiation over billions of years.

TRAPPIST-1 is like a slow-burning candle that will shine for about 900 times longer than the current age of the universe.

Eric Mamajek

NASA exoplanet scientist

However, old age does not necessarily mean that a planet's atmosphere has been eroded. Given that the TRAPPIST-1 planets have lower densities than Earth, it is possible that large reservoirs of volatile molecules such as water could produce thick atmospheres that would shield the planetary surfaces from harmful radiation. A thick atmosphere could also help redistribute heat to the dark sides of these tidally locked planets, increasing habitable real estate. But this could also backfire in a "runaway greenhouse" process, in which the atmosphere becomes so thick the planet surface overheats – as on Venus.

"If there is life on these planets, I would speculate that it has to be hardy life, because it has to be able to survive some potentially dire scenarios for billions of years," Burgasser said.

Fortunately, low-mass stars like TRAPPIST-1 have temperatures and brightnesses that remain relatively constant over trillions of years, punctuated by occasional magnetic flaring events. The lifetimes of tiny stars like TRAPPIST-1 are predicted to be much, much longer than the 13.7 billion-year age of the universe (the Sun, by comparison, has an expected lifetime of about 10 billion years).

"Stars much more massive than the Sun consume their fuel quickly, brightening over millions of years and exploding as supernovae," Mamajek said. "But TRAPPIST-1 is like a slow-burning candle that will shine for about 900 times longer than the current age of the universe."

Some of the clues Burgasser and Mamajek used to measure the age of TRAPPIST-1 included how fast the star is moving in its orbit around the Milky Way (speedier stars tend to be older), its atmosphere’s chemical composition, and how many flares TRAPPIST-1 had during observational periods. These variables all pointed to a star that is substantially older than our Sun.

Future observations with NASA's Hubble Space Telescope and upcoming James Webb Space Telescope may reveal whether these planets have atmospheres, and whether such atmospheres are like Earth's.

"These new results provide useful context for future observations of the TRAPPIST-1 planets, which could give us great insight into how planetary atmospheres form and evolve, and persist or not," said Tiffany Kataria, exoplanet scientist at JPL, who was not involved in the study.

Future observations with Spitzer could help scientists sharpen their estimates of the TRAPPIST-1 planets’ densities, which would inform their understanding of their compositions.

Elizabeth Landau

Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif.

818-354-6425

elizabeth.landau@jpl.nasa.gov