3 min read

In the year since NASA announced the seven Earth-sized planets of the TRAPPIST-1 system, scientists have been working hard to better understand these enticing worlds just 40 light-years away. Thanks to data from a combination of space- and ground-based telescopes, we know more about TRAPPIST-1 than any other planetary system besides our solar system.

A new study in the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics, using data from NASA's Spitzer and Kepler space telescopes, offers the best-yet picture of what these planets are made of. They used the telescope observations to calculate the densities more precisely than ever, then used those numbers in complex simulations. Researchers determined that all of the planets are mostly made of rock. Additionally, some have up to 5 percent of their mass in water, which is 250 times more than the oceans on Earth.

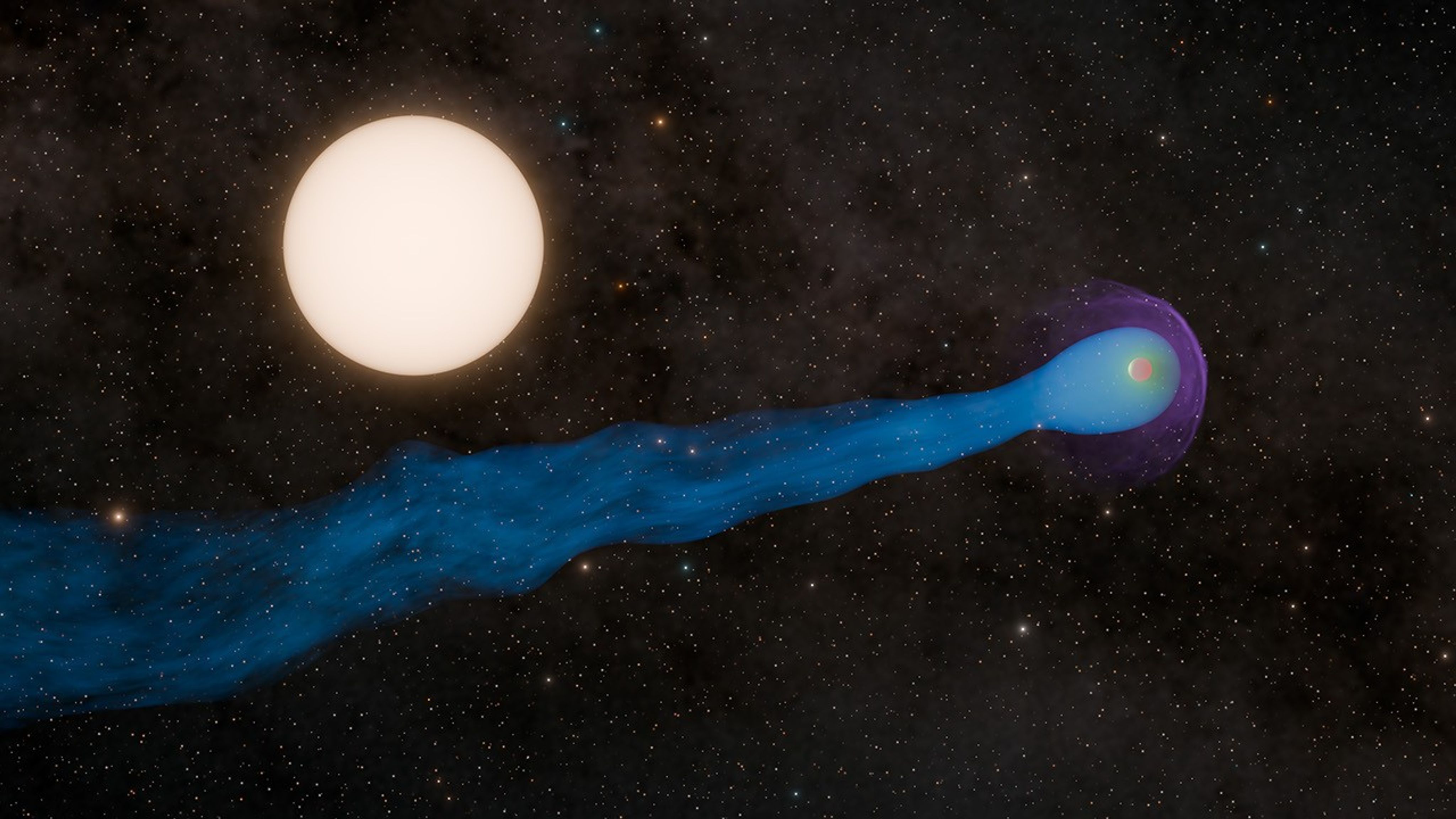

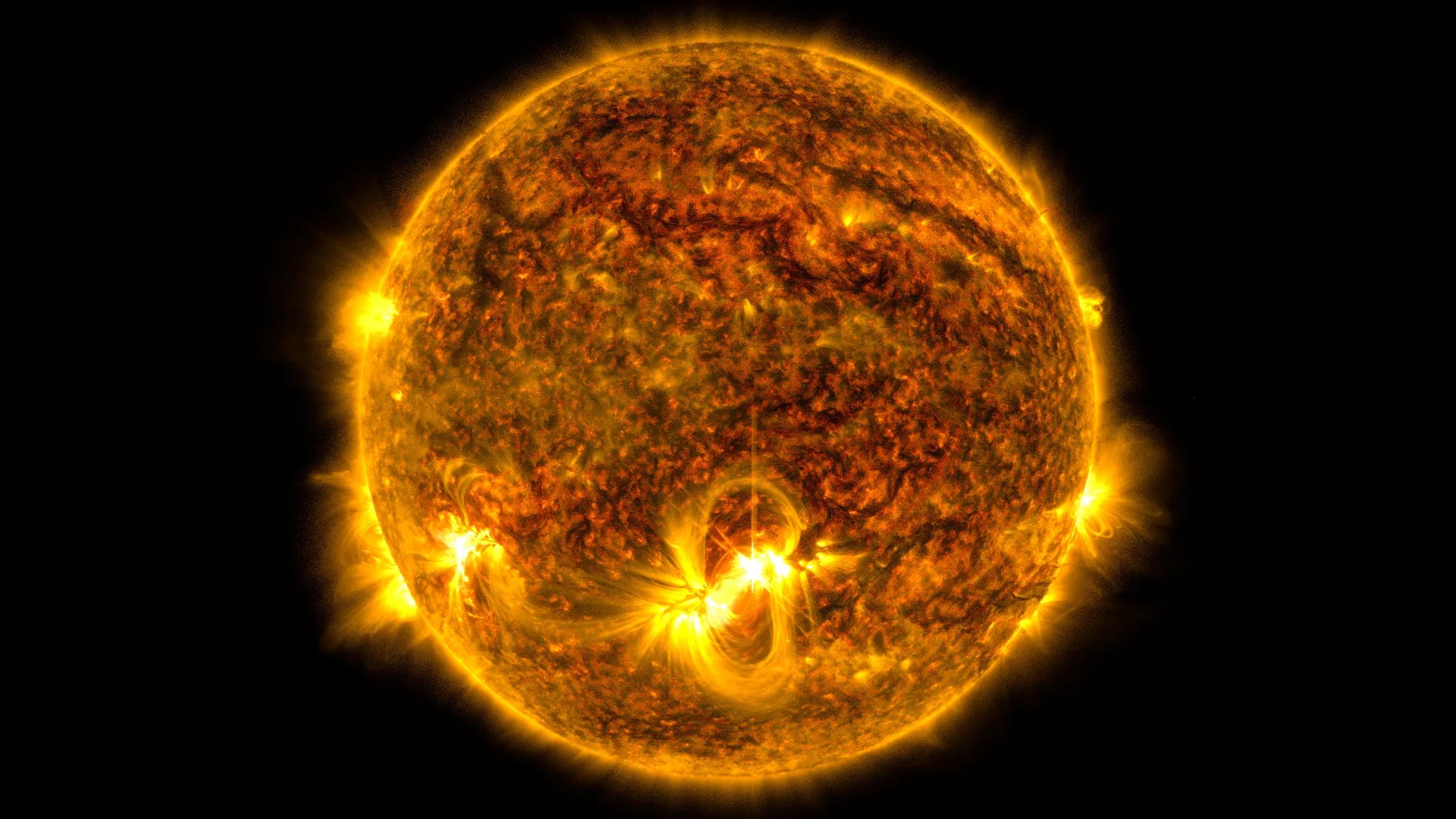

The form that water takes on TRAPPIST-1 planets would depend on how much heat they receive from their ultra-cool dwarf star, which is only about 9 percent as massive as our Sun. Planets closest to the star are more likely to host water in the form of atmospheric vapor, while those farther away may have water frozen on their surfaces as ice. TRAPPIST-1e is the rockiest planet of them all, but is still believed to have the potential to host some liquid water.

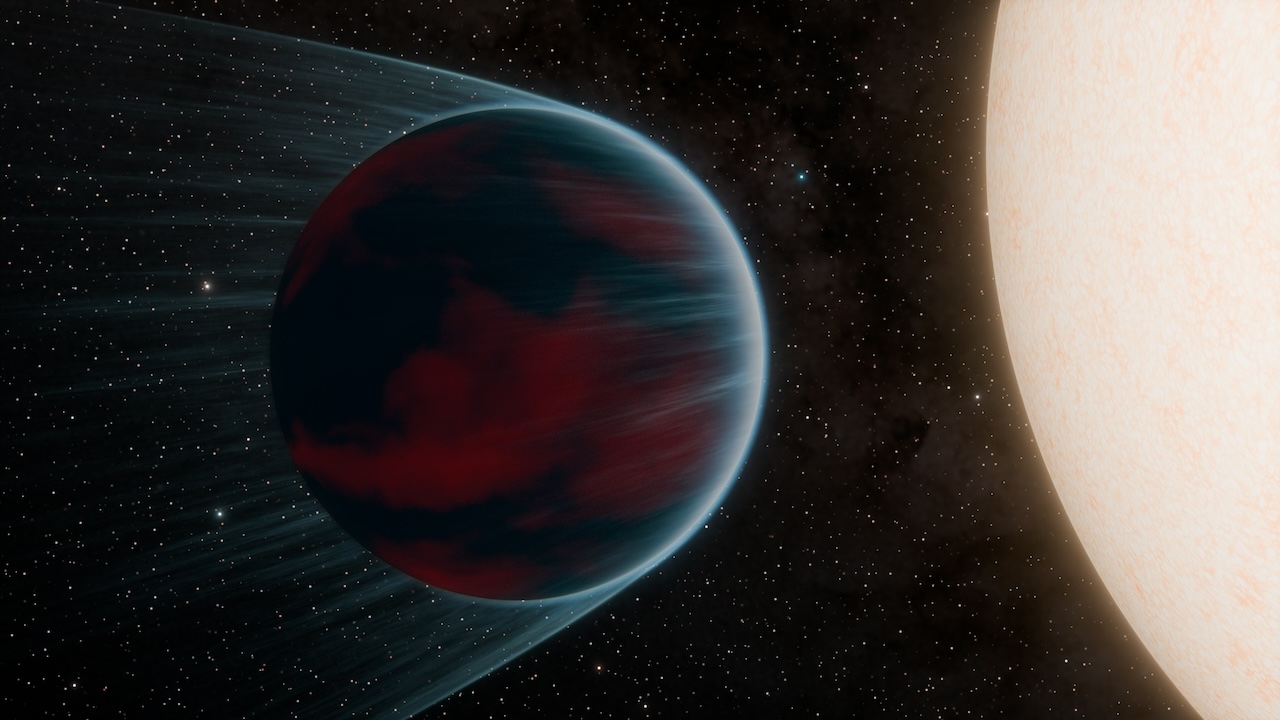

The question of the planets' atmospheres is also important for understanding whether liquid water could be present on these surfaces -- an essential ingredient for habitability. NASA's Hubble Space Telescope has now surveyed six of the seven TRAPPIST-1 planets, and new results on four of them are published in Nature Astronomy. In the new study, Hubble reveals that at least three of the TRAPPIST-1 planets -- d, e, and f -- do not seem to contain puffy, hydrogen-rich atmospheres like the gas giants of our own solar system. Hydrogen is a greenhouse gas, and would make these close-in planets hot and inhospitable to life.

In 2016, Hubble observations also did not find evidence for hydrogen atmospheres in c and d. These results and the new ones, instead, favor more compact atmospheres like those of Earth, Venus and Mars. Additional observations are needed to determine the hydrogen content of planet g's atmosphere.

Both studies help pave the way for NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope, scheduled to launch in 2019. Webb will probe deeper into the planetary atmospheres, searching for heavier gases such as carbon dioxide, methane, water and oxygen. The presence of such elements could offer hints of whether life could be present, or if the planets are habitable.

TRAPPIST-1 is named for the Transiting Planets and Planetesimals Small Telescope (TRAPPIST) in Chile, which discovered two of the seven TRAPPIST planets we know of today -- announced in February 2016. NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope, in collaboration with ground-based telescopes, confirmed these planets and uncovered the other five in the system.

For more information about TRAPPIST-1, visit:

For more information about Spitzer and Kepler’s findings, visit:

For more information about Hubble’s findings, visit: