3 min read

From detecting gravitational waves to combining those signals with light, scientists have been making strides in the field of multimessenger astronomy.

But wait – what is multimessenger astronomy? And why is it a big deal?

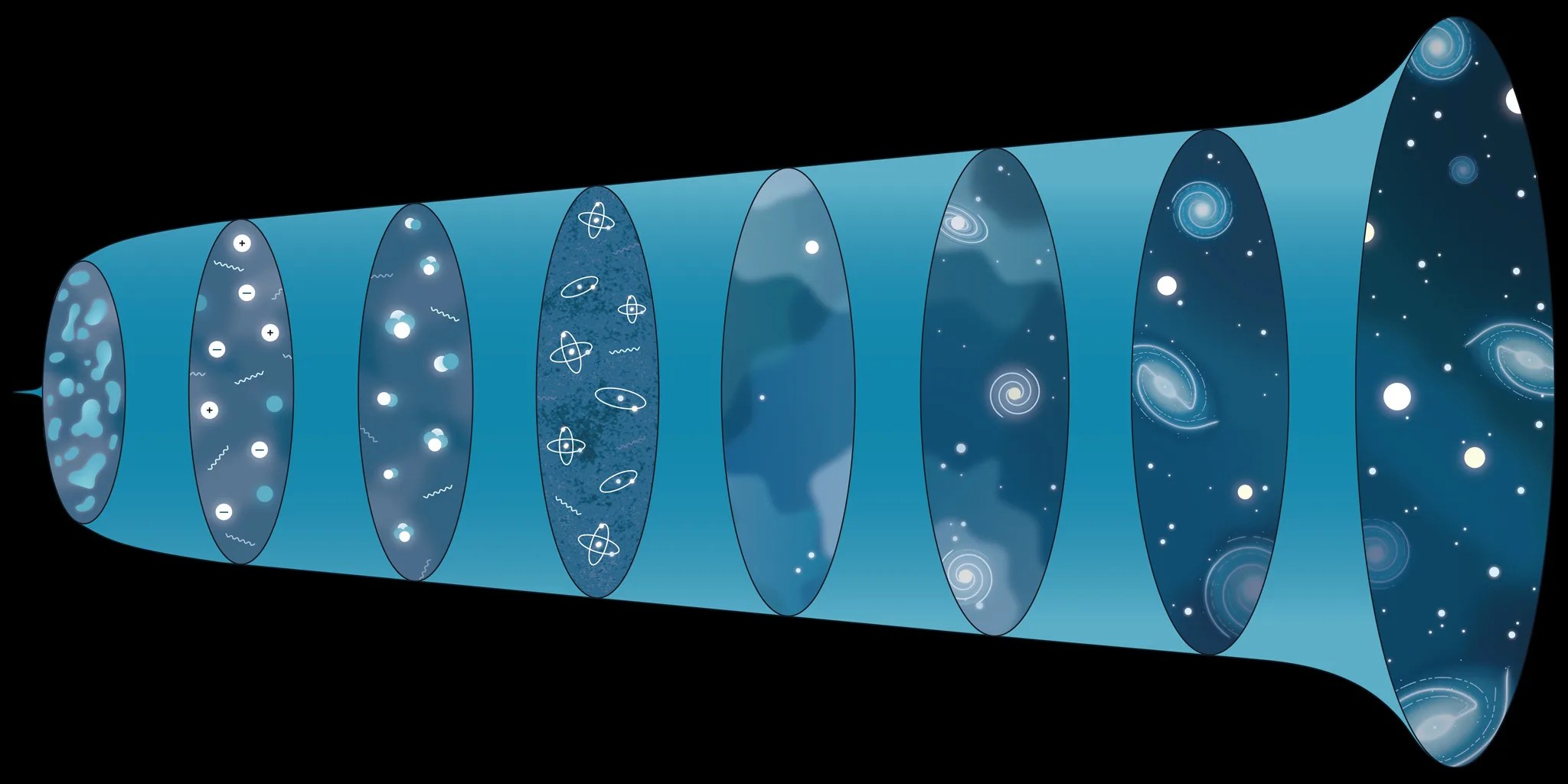

People learn about different objects through their senses: sight, touch, taste, hearing and smell. Similarly, multimessenger astronomy allows us to study the same astronomical object or event through a variety of “messengers,” which include light of all wavelengths, cosmic ray particles, gravitational waves, and neutrinos – speedy tiny particles that weigh almost nothing and rarely interact with anything. By receiving and combining different pieces of information from these different messengers, we can learn much more about these objects and events than we would from just one.

Lights, Detector, Action!

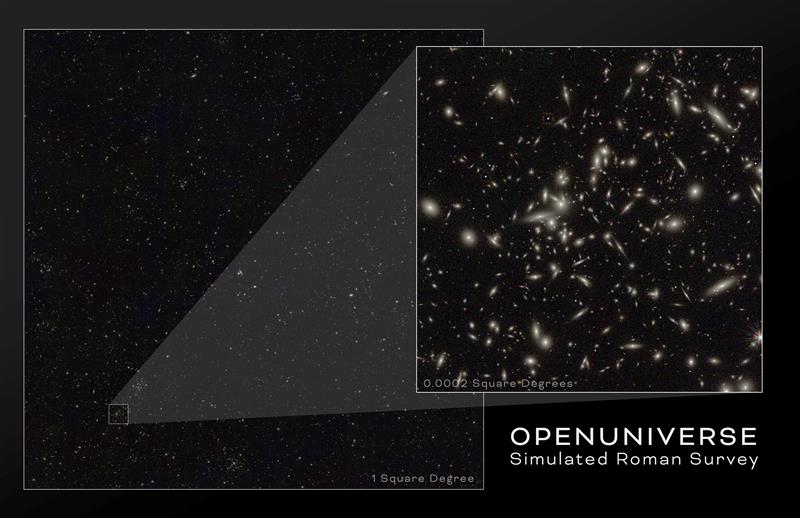

Much of what we know about the universe comes just from different wavelengths of light. We study the rotations of galaxies through radio waves and visible light, investigate the eating habits of black holes through X-rays and gamma rays, and peer into dusty star-forming regions through infrared light.

The Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope studies the universe by detecting gamma rays – the highest-energy form of light. This allows us to investigate some of the most extreme objects in the universe.

In 2017, Fermi was involved in two multimessenger firsts. In August it detected the very first light from a gravitational wave source, two merging neutron stars. In that instance, light and gravitational waves were the messengers that gave us a better understanding of the neutron stars and their explosive merger into a black hole.

Multimessenger Astronomy is Cool

Then, in September of that same year, it helped to combine another pair of messengers – light and neutrinos.

The IceCube Neutrino Observatory lies a mile under the ice in Antarctica and uses the ice itself to detect neutrinos. When IceCube caught a super-high-energy neutrino and traced its origin to a specific area of the sky, they alerted the astronomical community.

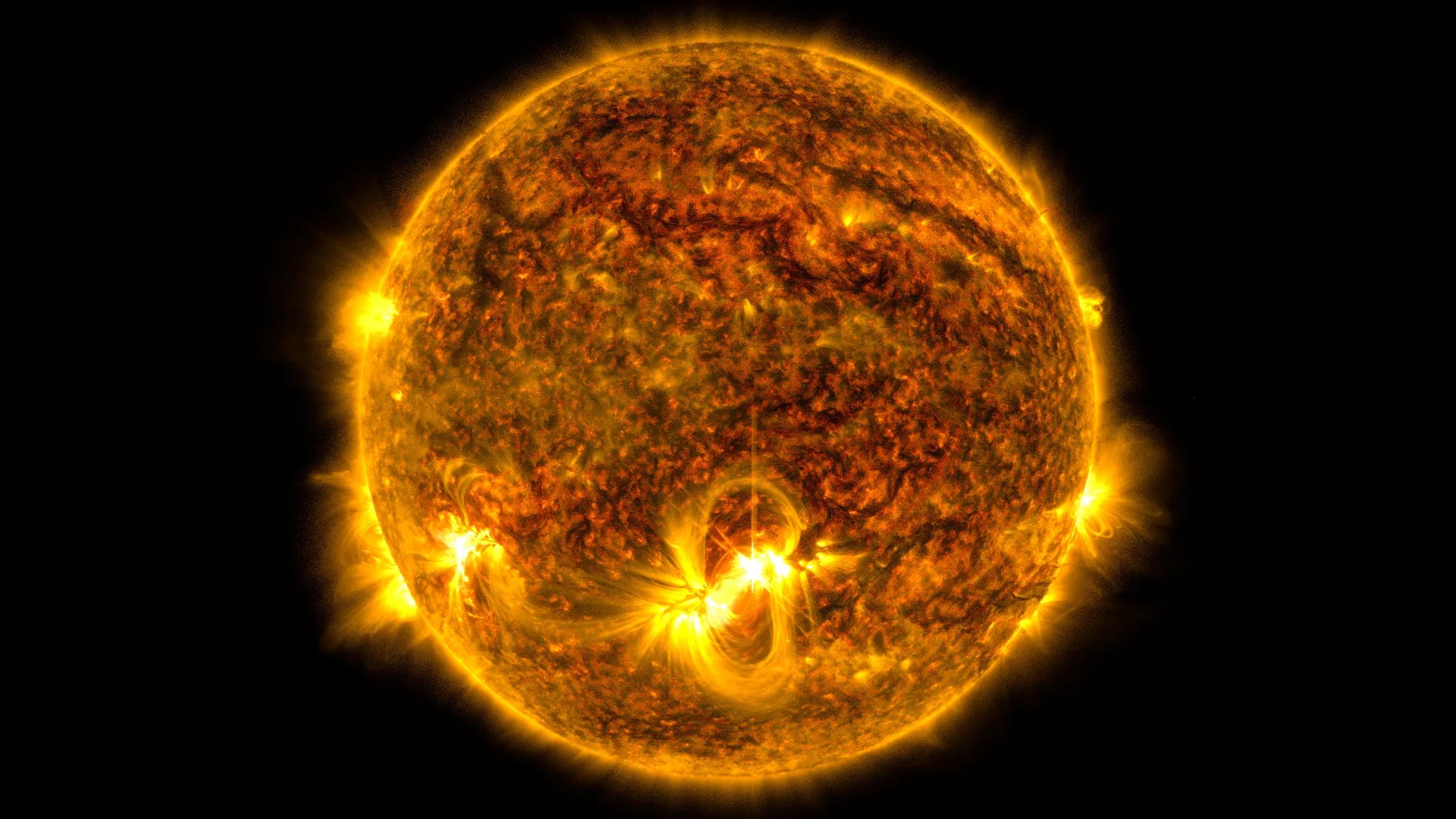

Fermi completes a scan of the entire sky about every three hours, monitoring thousands of blazars among all the bright gamma-ray sources it sees. Blazars are galaxies with supermassive black holes at their centers, and some of the material near the black hole shoots outward in a pair of fast-moving jets. In blazars, one of those jets points directly at us!

For months Fermi had observed a blazar producing more gamma rays than usual. Flaring is a common characteristic in blazars, so this did not attract special attention. But when the alert from IceCube came through about a neutrino coming from that same patch of sky, and the Fermi data were analyzed, this flare became a big deal!

IceCube, Fermi, and follow-up observations all linked the neutrino to a blazar called TXS 0506+056. For the very first time, this event connected a neutrino to a supermassive black hole.

Why is this such a big deal? And why haven’t we done it before? Detecting a neutrino is hard since it doesn’t interact easily with matter and can travel unaffected great distances through the universe. Neutrinos are passing through you right now and you can’t even feel a thing!

The neat thing about this discovery – and multimessenger astronomy in general – is how much more we can learn by combining observations. This blazar/neutrino connection, for example, tells us that it was protons being accelerated by the blazar’s jet. Our study of blazars, neutrinos, and other objects and events in the universe will continue with many more exciting multimessenger discoveries to come.