4 min read

PROJECT

Airborne Lunar Spectral Irradiance Instrument (air-LUSI)

SNAPSHOT

A new instrument flew aboard a high-altitude NASA plane to measure the Moon’s brightness and help Earth observing sensors make more accurate measurements.

A new instrument flew aboard NASA’s ER-2 airplane to measure the Moon’s brightness. Data from this instrument will eventually help other space-based sensors improve the Earth observations they collect.

The airborne Lunar Spectral Irradiance Instrument (air-LUSI) flew approximately 70,000 feet (about 21.3 km) above ground during multiple flights beginning Nov. 13 and wrapping up on Nov. 17, 2019 on the ER-2 from NASA’s Armstrong Flight Research Center in Palmdale, California.

Air-LUSI measured “how much sunlight is reflected by the Moon at various phases in order to accurately characterize it and expand how the Moon is used to calibrate Earth observing sensors,” said Kevin Turpie, a professor at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, leading the air-LUSI effort. Turpie and his team are funded by NASA’s Earth Science Division and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST).

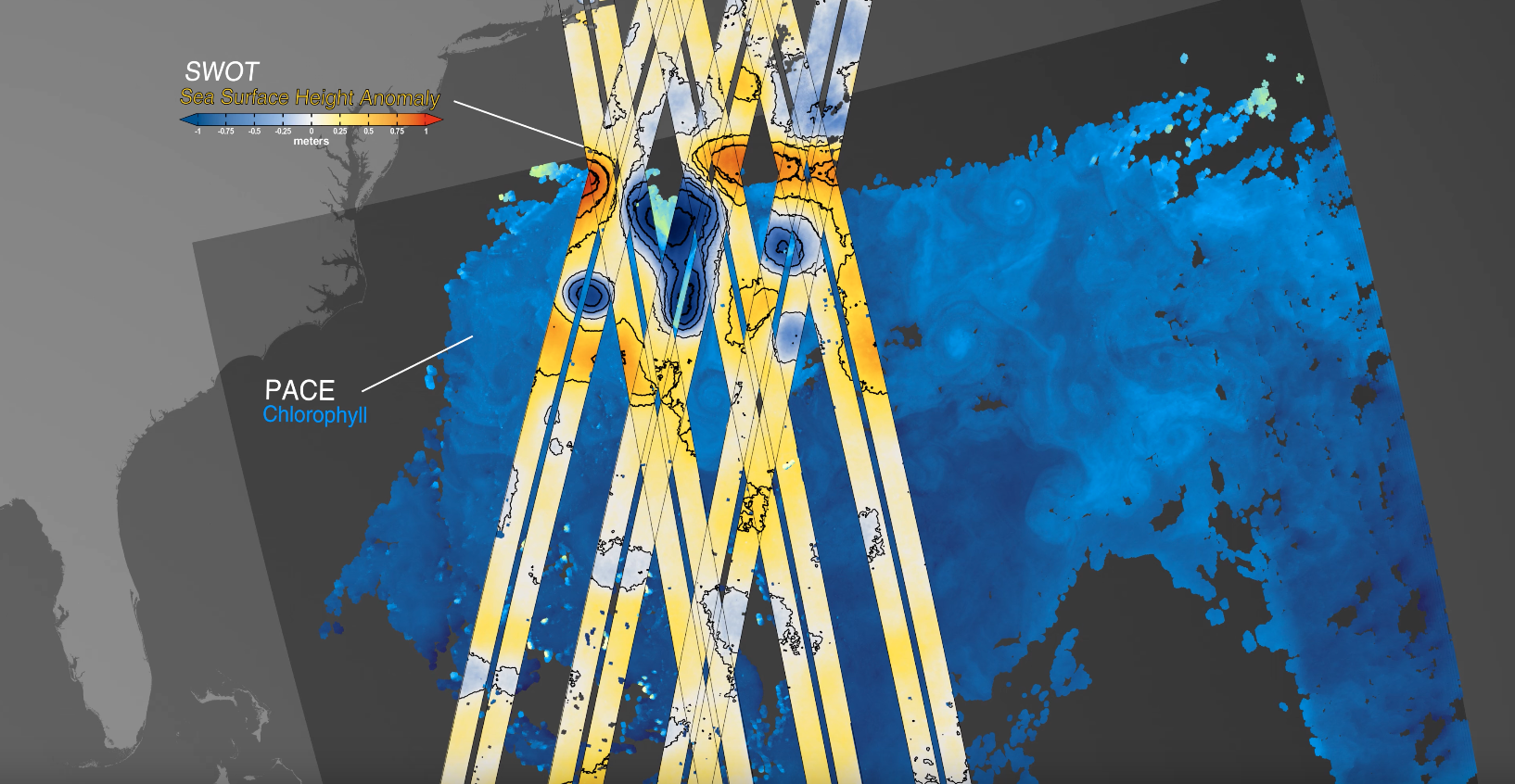

Air-LUSI’s novel instruments are able to obtain highly accurate lunar spectral irradiance measurements that will have the lowest ever uncertainty (less than 1%), Turpie said, which establishes the Moon as an absolute calibration reference and helps remote sensing scientists determine if Earth observing sensors—like the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometric Suite (VIIRS) aboard the NASA/NOAA/DOD Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership satellite and the NOAA-20 meteorological satellite—are recording actual changes on Earth or changes in their instruments.

Although Earth observing missions can look at the Moon at the same time and phase every month as a way to notice trends in their instruments’ sensitivity, they haven’t yet been able to use the Moon as an absolute calibration reference, Kurt Thome, a project scientist for Earth observing missions at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, said.

What does it mean to be an absolute calibration reference? If you compare two people standing next to each other, it’s easy to see which person is taller. However, if these two people are at opposite ends of the world, the only way to compare their heights would be with an absolute reference, like a ruler. Air-LUSI is aiming to make the Moon an absolute calibration reference, which means an instrument would only need to look at the Moon once to determine the instrument’s absolute sensitivity, and could compare looks over time to see if the instrument is changing, Thome said.

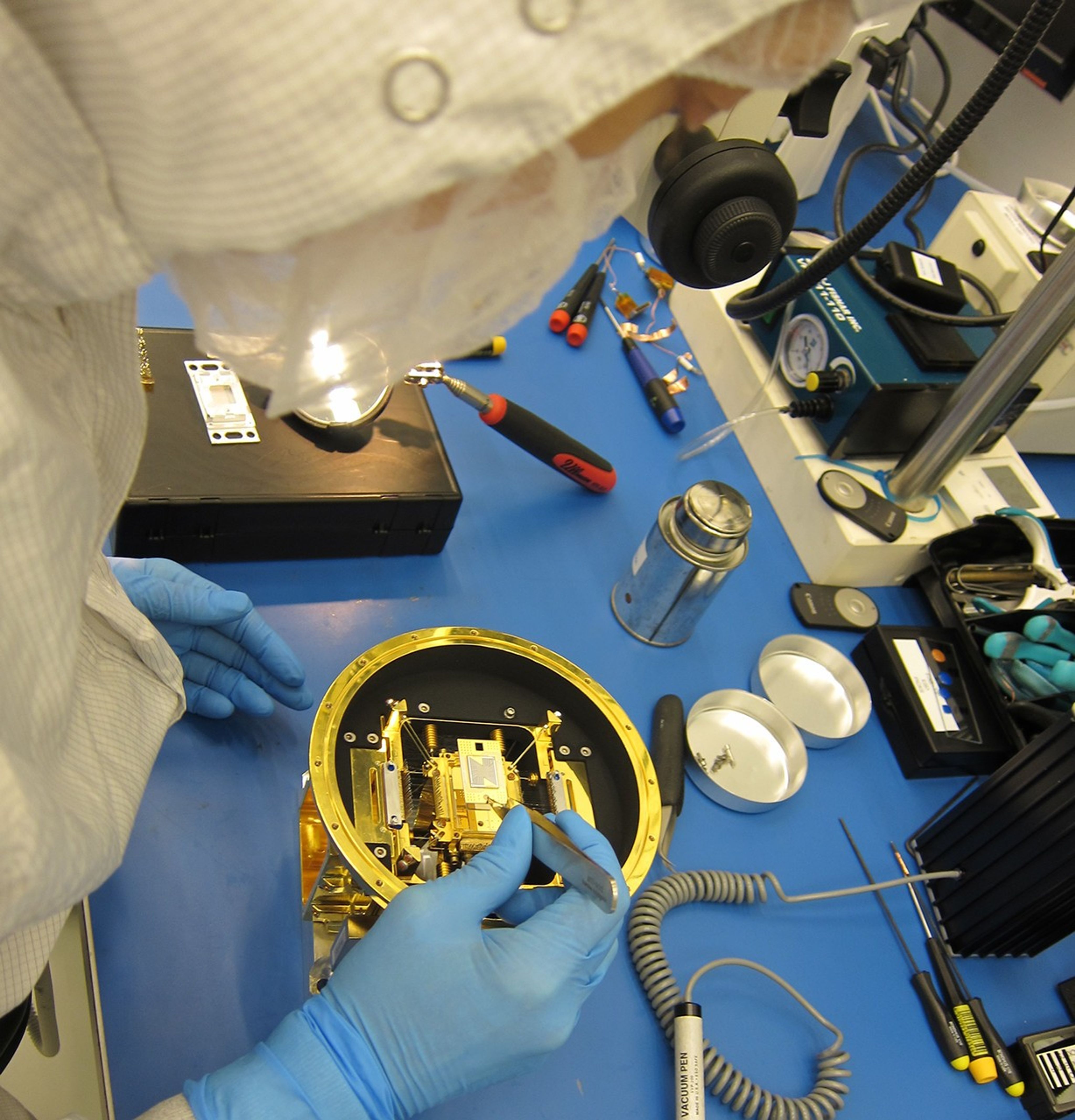

To gather information about the Moon, air-LUSI includes three subsystems, which require expertise from multiple organizations, said Turpie. His team includes people from NIST, the U.S. Geological Survey, the University of Guelph in Ontario, Canada and NASA.

The first component is called IRIS, short for Irradiance Instrument Subsystem, and was designed by NIST. It includes an instrument able to take precise measurements of the Moon while sitting in a temperature and pressure-controlled enclosure.

The second component is a robotic telescope mount called ARTEMIS (Autonomous, Robotic Telescope Mount Instrument Subsystem) designed and built by the University of Guelph. ARTEMIS has a camera that scans the sky until it finds the Moon and directs the telescope to point at it and keep it locked in place, regardless of aircraft motion.

The final component is the High-altitude ER-2 Adaptation, or HERA. HERA includes all the connective tissue, like cables and mounting equipment, which holds the instrument together and to the plane, as well as the thermal stabilizing components.

In the near future, an operational weather satellite would benefit from being able to look to the Moon as an absolute calibration reference, Thome said. Missions such as the currently-flying Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership (Suomi NPP) and Joint Polar Satellite System-20 (JPSS) satellites, as well as those to come in the future from both NOAA and their international partners could use this technology. Each satellite could calibrate its instruments by the Moon to compare how its sensors are holding up to the other satellites’ sensors, Thome said.

NASA’s upcoming Ocean Color Imager, aboard the Phytoplankton Aerosols Clouds and ocean Ecology (PACE) satellite, also intends to use the Moon for calibration, Turpie said.

“Air-LUSI’s Moon measurements make it easier for people to justify using the Moon to calibrate their instruments,” Thome said.

PROJECT LEAD

Kevin Turpie, University of Maryland, Baltimore County

SPONSORING ORGANIZATION

Earth Science Division, Airborne Instrument Technology Transition (AITT) Program